Mafia Movies: A Reader

John D. Calandra Italian American Institute has an impressive reputation for offering its audience conferences and for introducing compelling and fascinating books who put their focus on Italian-American and Italian issues.

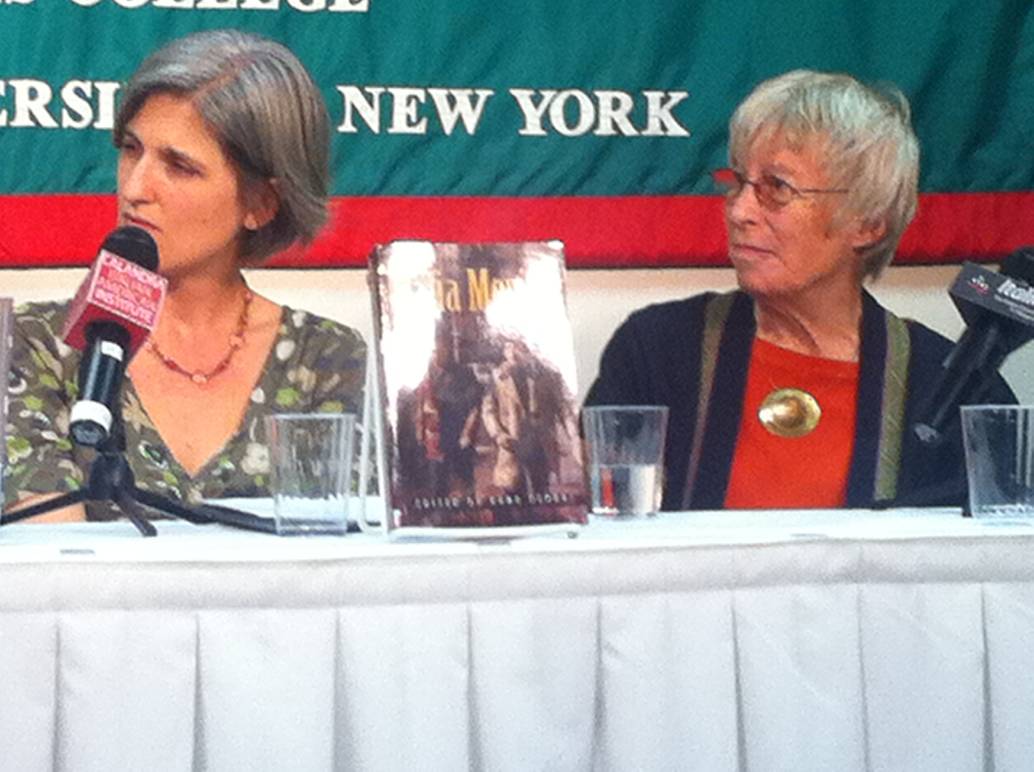

December 5th was no exception, the new book “Mafia Movies: A Reader” was presented by the Dean of the Institute, Anthony J. Tamburri, who briefly introduced the text, highlighting the main key features of this brilliant work, edited by Dana Renga and written by several well-known scholars in the academic community.

The first and maybe most interesting aspect of the book is the new approach to investigate a delicate topic. The aim of the volume lies in the identifying how Italian-Americans are portrayed over time by exploring the representation of gangsters onscreen. The richness of the diverse essays provides the basis to accomplishing this complex goal.

While introducing the first panel, “Historicizing the Imagined Mafia,” the event's moderation, Professor Renga, passionately commented on how the colume deals with several different directors who share a main feature: their interest in the mafia and corruption in the Italian or American system. Martin Scorsese, Elio Petri or Francis Ford Coppola are a few directors within its field.

Professor Renga even reminded the audience that men such as Peppino Impastato, Salvatore Giuliano, Paolo Borsellino, together with fictional characters like Tony Soprano, Don Vito and Michael Corleone have contributed in myriad ways to maintaining the myth of Italian and Italian-American mafia, or or off-screen.

Some of the questions the authors desire to answer are: “Is there a unique American or Italian cinema treating the mafia? How has the Godfather influenced films that come later, both in Italy and in the US? Why are Italian filmmakers more interested in making socially conscious films?”

Elizabeth Leake, Giancarlo Lombardi and Nelson Moe were the first panelists. Respectively from Columbia University, College of Staten Island and Barnard College

Professor Giancarlo Lombardi brilliantly analyzed the impact of a TV show like “The Sopranos” in the United States. Its capillarity and massive distribution has re-pictured mafia in the collective imagination, Tony Soprano and his universe have been crucial in changing the way Italian and Italian-American organized crime has been perceived in recent years.

The artistic quality of the Sopranos is undeniable, said Lombardi sincerely, but it's neglected in Italy, maybe for a poor choice of dubbing and a lacking interest in the public debate.

Professor Lombardi even noticed differences in the representation of mafia on Italian and American television by comparing “The Sopranos” to “La Piovra.”

David Chase, the creator of “The Sopranos”, made it clear that he was trying to glamorize the mafia but simultaneaously, his aim was to portray a slow and inexorable descent to hell, stated Professor Lombardi.

Professor Elizabeth Leake spoke about Tomasi's representation of Sicilians as “mafiosi” in his masterpiece The Leopard, and how it has been perceived by its audience. Leake briefly explained how the mafia was portrayed by Visconti in the movie adapted from the book.

“Not all the stereotypes come to do harm,” affirmed Professor Nelson Moe when describing the movie “Il Mafioso” in particular, and when the stereotype is purposely used by Lattuada, he stresses the differences between the “civilized” North and the “criminal” South, but in doing so he challenges and aims to provoke the viewer, claimed Professor Moe.

The second part of the conference focused on another subject, “Gender and Violence”, featuring Rebecca Bauman, George De Stefano and Jane and Peter Schneider.

Accomplished author George De Stefano talked about his essay, focusing on “the films in which sexuality and gender are important to the film itself, to the overall narrative.”

“What's considered proper female behavior and what is proper male behavior,” were issues that De Stefano addressed in his essay. It is crucial, he added, to stress that Italian-American and Italian criminal organized groups are male supremacists organizations, and that the classic “mafioso” is often depicted as in opposition to women and homosexuals.

Even in the real life “Cosa Nostra,” the Sicilian mafia is known to be very homophobic.

The films De Stefano wrote about are The Hundred Steps and Mary Forever. Marco Tullio Giordana, who directed the former, made clear suggestions that the film’s hero is probably a gay man, while in Mary Forever, young gay male prostitute is portrayed as a cross-dresser.

Rebecca Bauman, from Hofstra University, explained her essay in which she analyzes the sexual politics of loyalty in Prizzi's Honor. In this film the female protagonist is a hit-woman hired by the mafia, and when she is killed, said Bauman, she is considered a transgressor because of her gender and her role, which is uncomfortable for the whole organization. Hence she represents an ethos that doesn't conform to the mafia system.

Jane and Peter Schneider's contribution to the volume, instead, is not based on film but deals with real life implications and intersections between gender and violence. Jane Schneider is professor of anthropology at CUNY Graduate Center, and her husband teaches sociology at Fordham University. They were writing from a prospective of anthropological field workers, doing research in Sicily in the '60s, living in a rural town.

“A wonderful experience, actually knowing the mafiosi”, affirmed Jane Schneider.

One of the first “pentiti”, Vitale, killed at first because he wanted to prove himself to be a man and not a “pederast”, “there is a certain ambiguity”, professor Peter Schneider added.

The book Mafia Movies: A Reader is being published at a time when the mafia has been receiving international attention.

Roberto Saviano, writer of the book later turned into film, Gomorrah, arrived in the United States a few months ago; and while his testimony has been of vital importance in order for anyone to fully comprehend the dynamics and the mechanisms behind criminal organizations, it's important to maintain a critical eye in order to understand the wicked subtlety of the mafia when it interacts with people and its environment.

Perhaps it is best to avoid hasty judgments which often lead to prejudice.

If cinema really is “truth at twenty-four frames a second,” as Jean-Luc Godard once said, this book represents a way to deepen our knowledge about a stereotype that we see reflected in everyday society, to start asking questions about the creation of a myth through the lens of a camera, and most of all, to open our eyes to a phenomenon so deeply intricate and complex such as the mafia.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.