Another Turn of the Key. Nino Marano. 49 Years in Prison

>> IN ITALIANO

A crude story, but also one filled with humanity, that of Nino Marano, who spent almost 50 years behind bars. Years marked by many turned keys. A life of ups and downs. Characterized by brutal crimes that take place behind bars, but also by the love for his wife and children.

Nino Marano spends the first years of his sentence going in and out of the penitentiary. At the time he was in fact being investigated in various trials. “<< Marano, go get a job and don’t ever come back,>> Corporal Vasta told me as he handed me a suit, blue pants and a jacket of almost the same color. Who knows where he got them, but they were exactly my size and they were exactly what I needed to concretely feel like I was stepping into a different life.”

“I spent eight wonderful months with my Sarina. I felt like I was finally breathing. I had taken my life back into my hands, I looked for a job,” Nino Marano remembers. But then he is told that he still has to pay his due with justice. “I had to spend 16 months in jail to permanently close with the past...Such news would have sent anyone into despair, but not me...I wanted to pay my debt to justice in full. I willingly walked into the closest police station.”

From here, it gets hard to follow the unbelievable succession of events in which he is involved. Pages of criminal life, involving trials, escape attempts, sentences, prison transfers…

Alongside his personal story, the book traces decades of Italian history. Events that make their way into prison. Marano encounters the brigades, the ‘carceo duro’ measures known as ‘41 bis,’ all these societal changes as seen and experienced on the inside.

An almost unbelievable story, the one told by Emma D’Aquino, but true stories are often hard to believe. It all begins with a couple of stolen vegetables, following a childhood marked by hunger and poverty. The son of a sicilian worker, Marano had four brothers and grew up in a home that “smelled of hunger.”

His recollections give the novel a verist quality. “In the poor man’s house, everyone is right” … “the fork is for the wretched man” … so Giovanni Verga wrote in “I Malavoglia” (The House by the Medlar Tree)

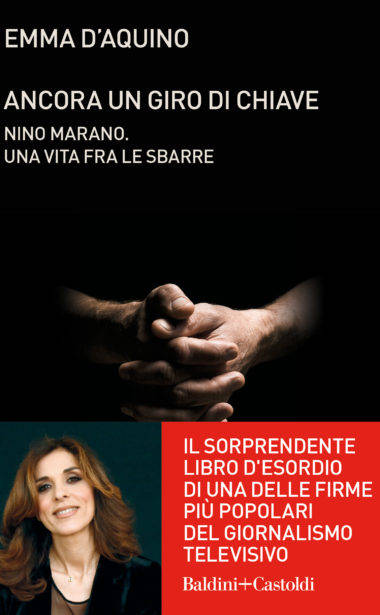

In “Ancora un giro di chiave. Nino Marano. Una vita fra le sbarre” (Another turn of the key. Nino Marano. A life behind bars) (Baldini Castoldi editions) - TG1 prime time news anchor, with an important reporting career - takes on a delicate theme.

The citicalities tied to life in prison are still numerous. According to Italian law, sentences should have an educational purpose with the goal - also through contact with the external world - of re-integrating convicts into society.

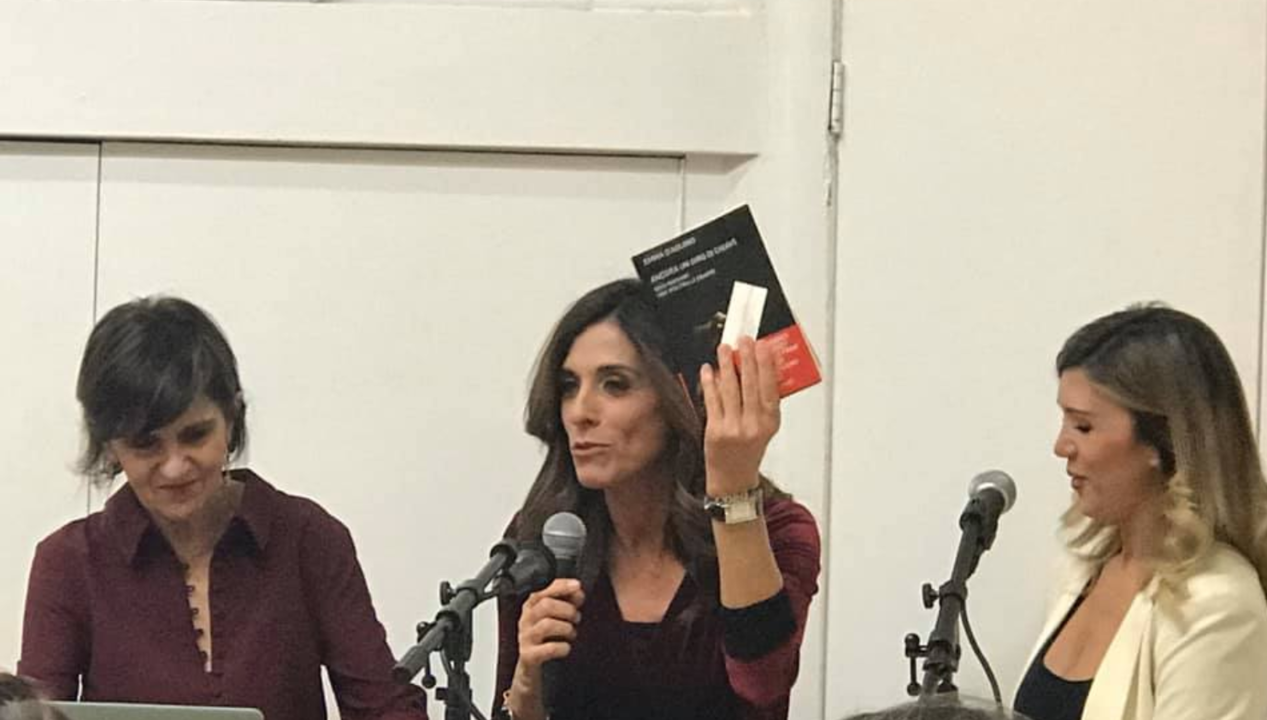

I would therefore like to continue here, with my pen, an open reflection that is incredibly difficult and vast, born during the double presentation of the book organized by Your Italian Hub in New York: the first one at St. John’s University with Professor Katia Passerini and her wonderful students; the second at Union Square Loft, where I conversed with Emma along with my colleague Francesca Di Matteo. Consul General Francesco Genuardi was there to introduce the event, while Ambassador Mariangela Zappia, the Permanent Representative of Italy to the United Nations, and the new Director of the Italian Trade Agency Antonino Laspina sat in the audience, speaking to the topic’s appeal.

I would like to clarify that I do not intend to justify Nino Marano in any way: he is undoubtedly a multiple murderer. A killer. But, to be clear, what initially landed him in jail was the theft of a few peppers and eggplants.

When we decided to present this book with Emma D’Aquino, I knew that it would be a hard one to explain. I had read it all in one breath last summer, and then returned to it several times, gone through its pages to review some passages. His story, though unique, leads to broader reflections.

The first one is: Emma D’Aquino - through the words of Nino Marano - recounts life in prison as it was decades ago, how much has changed in Italian penitentiaries since then? And the second one, since we are in New York: Is it true that the US prison system is even harsher? Also: how should we view the “re-educational function of sentences” when life in prison can actually push people towards violence? And finally: do we all agree that prison should have such a function rather than simply a form of payback?

Emma D’Aquino’s is an accurate, detached, controlled, careful tale by a deeply sensitive reporter.

She investigated, scrutinized, observed Nino Marano. A criminal with no affiliations to mafia clans, proud, a “one man show” of sorts, who from one penitentiary to another becomes time and again a murderer.

There are several aspects that stand out about him. In his words, we make out a sort of moral code, his “immoral morals.” Something primordial, ancestral, that comes from his humble and misfortunate origins, a clear lack of civic culture.

Based on a sort of “necessary evil,” which Nino considers a weapon of legitimate defense against the injustices he and others face. And for Nino legitimate defense justifies violence.

“From my encounters with Nino, I learned that he acts based on a specific personal ethical code, founded on the respect of the innocent, who as such shouldn’t be harmed but protected (and prison guards belonged to this category)” writes Emma D’Aquino. She continues: “I believe he has been the victim of his inability to distinguish clearly between good and evil, without nuance or contamination. A victim of the role of censor he tried to take on within a world deprived of moral rules.”

And next to this man, far away but intimately close, is a woman: his wife. Sarina never abandoned him and his words spell out his love for her. The pages dedicated to this couple, to their children, are very intense. So, he’s a ruthless man, but also deep and attentive towards his wife Sarina, whom he loves and who loves him back.

I can’t help but wonder: did he become violent in prison or was he already violent? Had he been born in a different social context would he have become the same man? Could his life have taken a different path?

It’s clear that we are all the same to begin with. It’s clear that prison did not help Marano to “redeem” himself, as the Italian law and international resolutions to respect human dignity would have it. Instead, detainees are left to fend for themselves "in the wild."

His sentence seems to lead to new deviations. Is there no hope then for Nino Marano? That’s not the case, he too had his chances, especially in the last years. As Italian prisons slowly changed, some people offered him a hand.

At the end of the book there are two chapters. One is titled “The Metamorphosis” and the other “Professor Gioia.”

“My rebirth is derived of a long process, and for it I have to thank those who in these years in prison have helped me to understand, to look inside, to become the man I am today. The teachers, the volunteers, the directors. At the same time, I don’t believe that what happened to me was all my fault, and I can’t say that I have really repented for all that I’ve done in prison.” These words paint the portrait of a man full of contradictions, proud but “tormented by memories,” as the author writes.

However, the book leaves us with a sense of hope, beyond the tragic story it tells. It traces a path towards “redemption.” Many questions about how to live and build a life behind bars today remain.

I want to conclude by inviting you to read Emma D’Aquino’s beautiful book. To reflect on these deeply human nuances.

----

Ancora un giro di chiave: Nino Marano. Una vita tra le sbarre

by Emma D’Aquino

on Amazon

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.