Dacia Maraini, Memories From a Japanese War Camp

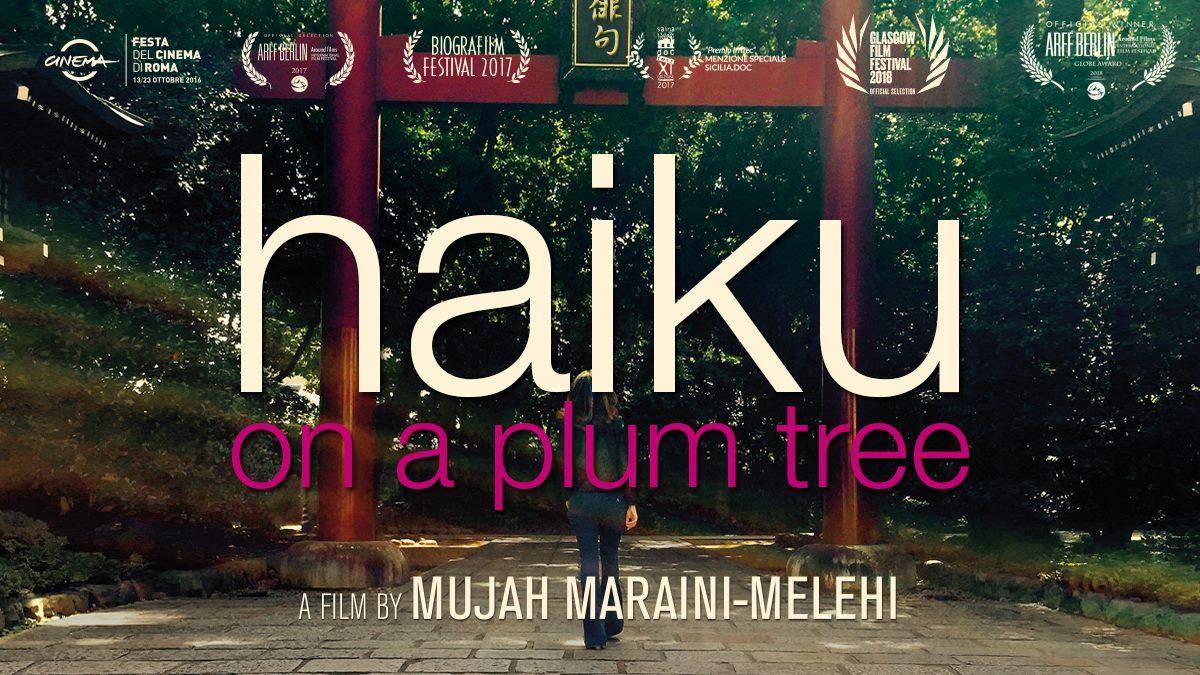

In her directing debut, "Haiku on a Plum Tree", Mujah Maraini-Melehi takes us along her journey to unravel her family’s history, and particularly the little-known story of their years spent in a Japanese concentration camp during World War II. It was the price the director’s grandparents (Dacia’s parents), the anthropologist Fosco Maraini and the Sicilian princess and artist Topazia Alliata, paid for refusing to sign a document adhering to the Republic of Salò, the fascist puppet state put in place during the German occupation of Italy from September 1943 to May 1945.

An Idyllic Life Until...

The director's grandparents moved to Japan in 1938 where Fosco Maraini conducted research. There they lived what from the numerous photographs and journal entries presented in the film appears to have been a pleasant, idyllic life, with their three daughters, Dacia, Yuki, and Toni (Mujah’s mother). Now a renown author, Dacia Maraini remembers how as a child she spoke the language fluently “better than Italian”, she went to Japanese school, had Japanese friends, felt the culture as her own, and this feeling persisted through her time in the camp and up until today.

Until 1943, when officials showed up at their house demanding they sign papers declaring their allegiance to the newly instated Republic of Salò, the puppet state headed by Mussolini and controlled by Nazi Germany. Both Fosco and Topazia refused to sign. Shortly after, all five family members, including the children, now considered traitors, were taken to a Japanese prison camp, where they stayed until the end of the war, facing hunger, cold, torture and daily humiliations.

Facing Painful Memories

Maraini-Melehi explains that she felt compelled to make this film in order to understand and process her family history. This project has given her and the rest of the family the opportunity to begin discussing this difficult and painful topic. Topazia, who passed away at age 102 in 2015 while Mujah was still working on the film, narrates most of the story and her drawings and diary entries appear constantly throughout the film. Dacia Maraini, Mujah’s aunt, and Toni Maraini, her mother, also appear as narrators and share their memories.

The film is in fact mostly about memory, about the urgency of passing down stories which are deeply personal but also universal. The importance of talking about the past, of remembering what happened, even and especially if it is difficult, painful, and in some cases shameful, is a theme that is being increasingly discussed nowadays, in many places including Italy and other countries where certain extremist ideologies which were thought to be in the past are threatening to make a comeback.

In the film, Dacia says that when her parents left Italy in ‘38, “Europe was drunk on racism.” While racism and hate may look different today, be less “outspoken” or “direct” - for example, during the discussion she remembers how in those times people theorized about race, claiming it was a scientific, provable fact that some races were superior to others - we cannot dupe ourselves into believing that it no longer exists. “Racism went out the front door and came back through the window” the author comments.

The rejection of racism is a central aspect of the film. It’s what lead Fosco and Topazia to make the choice that would affect the lives of the entire family. Dacia insists that her parents’ decision not to sign in allegiance to the Republic of Salò was not a political act “they did not belong to any political party”, it was a direct consequence of the fact that they were thoroughly and unequivocally against racism.

Memory and Hate

Another important aspect of the film is how it emphasizes the distinction between memory and hate. Though not all the family members have the same relationship to Japan, none of them feel hatred or resentment towards the country and its people. This can also be said of the film itself, which stylistically is a celebration of Japanese culture, as it makes use of Japanese music and theatrical practices, particularly through the use of puppets and a specific type of screens belonging to a 17th century tradition which was itself long forgotten even in Japan and is now being rediscovered, making it the perfect medium for realizing a film about memory. While the use of puppets gives the viewer the possibility to project onto the film more than live actors would and thus renders the universal aspect of the Maraini family’s story.

Even as a child, Dacia separated the Japanese people from the regime that incarcerated and tortured them. This subtle distinction is fundamental in order to avoid perpetuating a cycle of hate. Which is why it is so important for the people who have had such complex and difficult experiences to talk about them, to explain them (and for everyone else to listen). The author admits that, though she does mention her family’s life in Japan and the fact that they spent time in concentration camps in passing in her famous memoir Bagheria, she has never discussed it completely. “Before dying, I want to write a book specifically about this, about my experience and how I lived it as a child,” she says.

We can’t wait to read it.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.