Walls and Bans. A View from San Diego

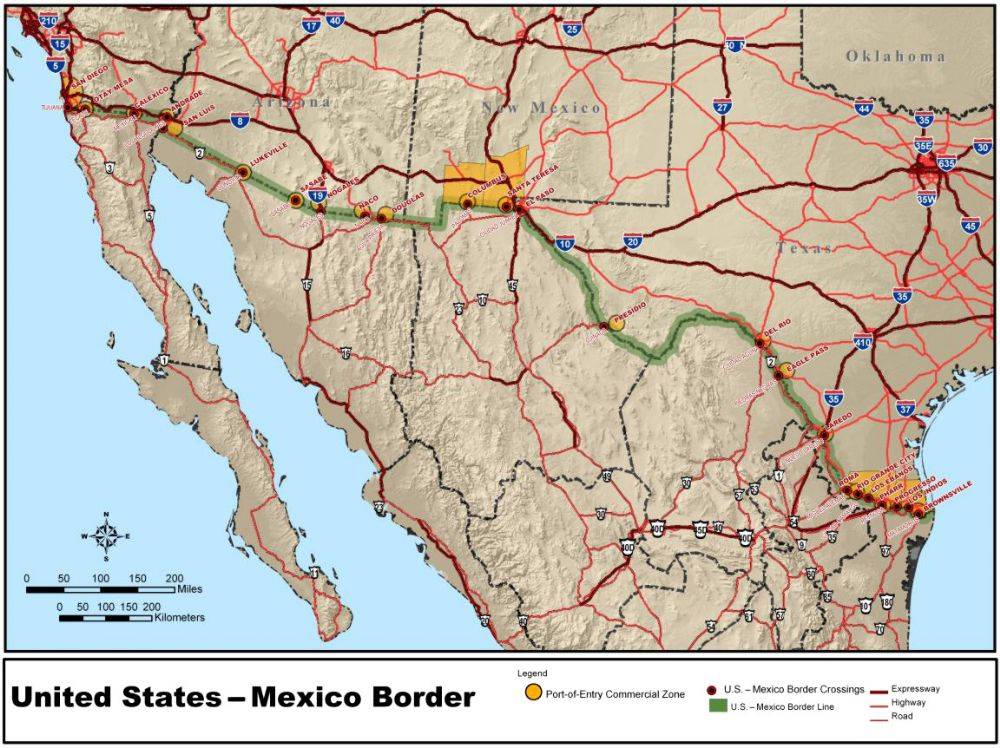

On Wednesday, January 25 an order was signed regarding the construction of the phantomatic wall on the Southern border. To anybody living in the greater San Diego-Tijuana area and familiar with the daily hundreds of thousands crossings and re-crossings of what is considered the most trafficked border on the globe, the idea of building a wall is simply preposterous, not to mention unnecessary, because the wall already exists.

Useless Walls

While it is largely ignored by most San Diegans, it is very present in the life of many other transnational citizens, who inhabit both locations despite the institutional and legal efforts to keep them apart. Many of my students belong to both cultures and navigate them despite their contradictions. The wall is a reminder of the imperialistic legacy perpetrated by nation-states, it separates families and fosters inequalities, but it is also a source of constant creative resistance and civic engagement, which not only highlight our differences, but emphasize our similarities. No matter how high, or wide, or militarized, the wall has never discouraged people from crossing it, legally or illegally, in the same way in which the vast and daunting expanse of the Mediterranean has not deterred migrants from attempting to reach its northern shores. All that these real or metaphorical walls have really illuminated is the resilience and tenacity of those who traverse them despite all odds.

Useless Bans

To cap a contentious first week in office, on Friday January 27 another incendiary order was issued banning entry into the US to immigrants from 7 primarily Muslim countries, including Iraq, Iran, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya and Somalia, and effectively barring entrance to all refugees from around the world. While this selection is highly arbitrary, it is reminiscent of previous moments in American history when certain nationalities were excluded and targeted. Most notable in the Italian case was the status of enemy aliens assigned for a time to Italians during WWII, a classification which in San Diego implied curfews and confiscations from radios to fishing boats, and in some occasions internments and forced relocations.

What strikes me the most about the current immigration ban is that two of the countries, Libya and Somalia, were Italian colonies in a not so distant past. It is, of course, difficult and inadvisable to draw a single, direct causal connection between Italy’s confounding and still largely understudied colonial past and the current situation, but it is undeniable that the history we are witnessing today is a result of a number of actions and inactions that have taken place in the past. The historical legacy of colonialism and the subsequent association with the respective dictatorships have led to much political instability, ultimately influencing their current internal and international assets. While during Fascism Libya was hailed as “la quarta sponda” (the Forth Shore) of a supposed Mediterranean empire, today Italy would gladly disavow any implication in the mass migration departing from that country and including a considerable number of people from its former colonies in the Horn of Africa, who risk their lives in the desert before taking to sea.

In Italy today the most acute voices denouncing the damages of colonialism and its postcolonial repercussions comes from the literature of Afro-Italian women writers whose origins are rooted in that region and whose families have been displaced by the war and unrest constantly plaguing it, as in the case of Igiaba Scego, Cristina Ali Farah and Shirin Ramzanali Fazel, all of Somali heritage, and all representing a global diaspora that extends across continents, from Mogadishu to Rome, to London, to San Diego and beyond.

Trying to make sense of all this

How to make sense of these seemingly disparate contemporary crises and historical legacies? We should begin by recognizing how similar the current ban and wall rhetoric are to previous acts of exclusion that have affected different national groups, including Italians, as other Italian-American scholars have already suggested. This allows us to think in terms of alliances among diverse communities that have, at different moments, experienced an analogous, albeit not identical, discrimination. Moreover, if we consider the long history of Italian emigration and compare it to other diasporas, we may find that these movements, either voluntary or dictated by untenable conditions, largely superseded the constraints imposed on people by the rules of individual nation-states. We are still working primarily within nationalist frameworks – and the trend of late is certainly veering toward dangerous ethnocentric populisms across the West – but laws and regulations can only temporarily control flows. None of the restrictive measures enacted last week can contain these displaced populations in the long run, nor stop their movement because human experience, comprising habits, desires, and needs, exceeds the law.

Policy makers, especially those lacking political will and imagination, have a long way to go to properly address the complex transnational migratory configurations that make people move across and beyond multiple national confines as the result of imperialism and globalization. In other words, human and family relations, of Italians, Somalis and all other populations, are far ahead in their diasporic networks across continents than near-sighted interpretations purporting to limit their residence only to specific territorial boundaries. The history of Italian migration, for one, has never been a one-way affair, but has always been one of triangulations, of departures and returns, of arrivals and relocations, and the rules imposed by borders and boundaries, while obviously detrimental, have never stopped their circulation. So perhaps the toughest walls to fight are not the physical ones, but those of closed minds.

* Clarissa Clò is Associate Professor of Italian & European Studies and Director of the Italian Studies Program, San Diego State University.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.