Losing (and gaining) my ethnicity

When Romano Prodi lost a vote of confidence in the Italian January election debacle, I had only one response: I wished my roots were English. It wasn’t just the humiliation of watching yet another government collapse (sixty-one since 1945). No, my inclinations toward Anglophilia came after reading the New York Times coverage of the parliamentary scene. Emotions ran so high (now, that’s a surprise), that a senator “rushed in fury to the desk of a colleague, Stefano Cusumano, and taunted and apparently tried to attack him. Mr. Cusumano, 60, reportedly cried, then collapsed.”

Cried, then collapsed? Oh my, I know this film -- I’ve been to enough Sunday family gatherings over the years. Bad enough that Mr. Cusumano brings to mind Tony Soprano’s neighbor (Cusamano), but the Times also ran a picture of the man sprawled on the ground so we could all see Italians being Italians. So yes, I wanted to go to London and watch those highly articulate and argumentative members of Parliament throw out pithy remarks and refrain from physically attacking their adversaries.

I remember my mother proudly telling me when I was young that my southern Italian father was often confused for being English. My dark-haired, green-eyed father, whose name was Henry, could easily “pass.” He was quiet, reserved, the opposite of those fiery men.

So I know this type of man, and when I want to get my dose of them (escaping from my mother’s emotional, scream-until-they-faint side of my Italian family), I usually read my favorite English writers. Julian Barnes is on the top of that list, and I recently ordered his new book, Nothing to be Frightened of, on Amazon.uk. I had read about this book – a meditation on death, God, and family -- (sounded light) and decided I couldn’t wait six months until it was published here. I have turned to Julian Barnes many times for his insights and wry observations, and when it came to the most vital subject -- God, death, and our place in the universe -- I was happy to place myself in his massively talented hands.

Yet, once having finished this book, I began to feel content about being Italian-American again. I realize that no matter how much I long for English rationalists, I need Italian emoters. I adore Julian Barnes as a novelist and essayist, but as a memoirist Barnes is just too cool for me, withholding from family members the sympathy he gives to his fictional creations. Here is Barnes’s on viewing the body of his dead mother: “Wanting to see her dead came more, I admit, from writerly curiosity than filial feeling; but there was a bidding farewell to be done, for all my long exasperation with her.”

His tone toward his mother remains critical and distant throughout the book; and he explains that of his mother’s two sons, he, the novelist is the more sensitive and affectionate. His philosopher brother, the ultimate rationalist, thinks Julian can be “soppy.”

Bloody hell – bring back the mammoni, the ultimate mamma's boys.

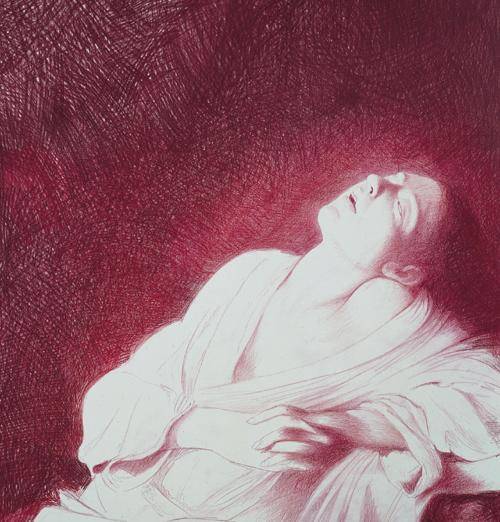

For despite the operatic character of the Italian that has been replayed for us throughout the centuries – the screaming, the crying, the fighting, the grief – if I had to choose (and I don't because this is my genetic material), I'll take melodramatic overtures over bloodless rationalism -- the irrepressible desire to be alive in a dark, chaotic universe. Italians expect the collapsed man to get up again, gasping for every ounce of breath until his body ultimately deserts him. His mother might even be at his side. At least that is the myth by which we live.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.