Immigrants in the Mediterranean: Italy, Libya and Politics

ROME -- In 2016 the brilliant Italian film director Gianfranco Rosi produced a superb movie, "Fuocoammare" (in English, "Fire at Sea"). "Fuocoammare" is a documentary which also involves an element of fiction. It describes life at Lampedusa, the Sicilian island besieged by migrants arriving by boat from all over the Mediterranean or, as is also the case, not arriving because they have drowned en route. At the 2016 Berlin film festival Rosi was awarded the Golden Bear; in 2017 "Fuocoammare" was Italy's selection for an Oscar.

Rosi's film is all the more important today, when all of Italy is en route to becoming a Lampedusa. The government is struggling to find a way to manage those migrants already here, while begging help from all quarters in managing the continuing flood of arrivals and seeking ways to avoid more arrivals.

This is no easy task. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency UNHCR, by the end of 2016, conflict and persecution had uprooted 65.6 million people from their homes -- that is, 20 people uprooted every minute last year. Those already in Italy make up 8.3% of the population; of these, over half (55%) are women. Twelve percent have university degrees but one out of three (34%) performs manual labor tasks like picking fruit and vegetables on farms.

In Italy, over 95,000 migrants arrived between Jan. 1 and July 31 this year. Nevertheless, slightly fewer arrived than during the same period in 2016, even though a headline in the daily "Il Giornale" proclaimed that "Italy is invaded by migrants." The greatest number, 18%, came from Nigeria while the arrivals from Bangladesh were 10.4% of the total; from Guinea, 10%; and from the Ivory Coast, 9.3%. Their landing points were, first, Sicily, with 61% (down from the previous 90%), followed by Calabria, 23%: Campania, 7%, and Puglia and Sardinia, 5% each. (See: http://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2017/6/5941561f4/forced-displacement-worldwide-its-highest-decades.html)

Italian President Sergo Mattarella has denounced the situation as becoming unmanageable. "A country on its own simply cannot handle this," he said in June. "Even a country as great and open as ours needs international cooperation, but some European countries are insensitive... The migration phenomenon must be managed while at the same time citizens' security be ensured." For Premier Paolo Gentiloni, "We don't want to aggravate the situation but we do ask other European countries to stop just looking the other way. This is no longer tolerable."

As their words show, Italy is essentially humanitarian-oriented, but is caught between a rock and a hard place, or between the desire to help the migrants and to stop the migrating. One way being urged is to stop at source the migrants and the human traffickers who run the rickety boats. This depends upon the unproven premise that some organizations which have been stepping in to save the refugees from drowning have aided and abetted the traffickers. Even if untrue, some argue that their saving of lives encourages still more migration.

As a result, the recent goal, ratified by the two countries signing an agreement, has been to halt the flow between eLibya and Italy. Seeking further results, European and sub-Saharan foreign ministry representatives met to try to block the migrants for screening before they leave their home countries like Mali, Niger, Ethiopia, Chad and Sudan.

Has this so-called the diplomatic approach worked? Not very well, as the testimonials of imprisonment and photographs of ghastly, over-crowded "holding centers" in Libya show. The Libyans show faint respect for human rights, among other things, and although Italian authorities say they are asking "guarantees" from Libya on this, no one expects such guarantees to arrive soon.

In July Italy also tacked on a controversial "code of conduct" accord with Libya that permitted armed guards to be aboard rescue boats. Medici Senza Frontiere refused to sign this agreement. See:http://www.medicisenzafrontiere.it/notizie/video/5-motivi-non-bloccare-migranti-e-rifugiati-libia

The recent reduction of departures from the Libyan coast is being celebrated as if a great success to avoid drownings at sea and to fight against the traffickers. "But we know very well what is happening in Libya," said Medici Senza Frontiera in an open letter Sept. 7 to Premier Gentiloni. Their view is that the EU politicies and financing are contributing to a reduction in boats parting from Libya, but in practice, "This only increases a criminal system of abuses.... People [confined in Libya] are treated like merchandise to be exploited.... The women are abused and than obliged to call their families to beg for money to be freed."

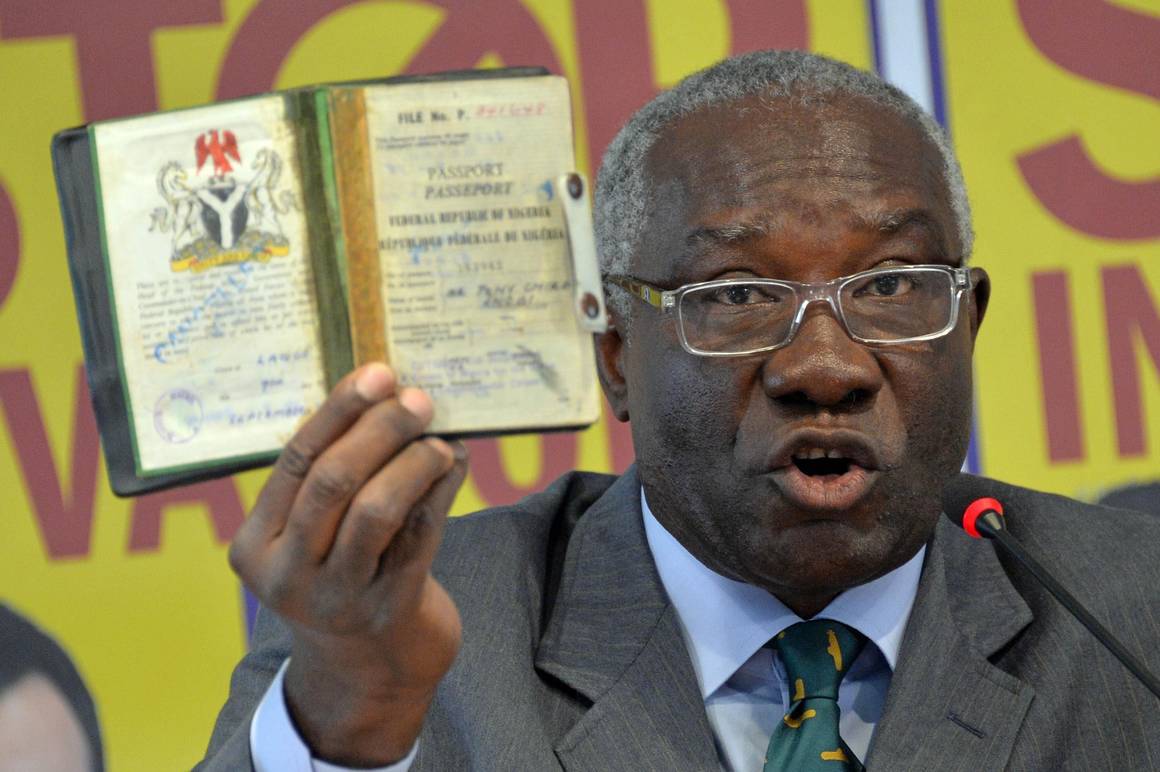

The problems of immigration continue to grow as a useful political tool, especially in the Northern League, which campaigns noisily against immigrants. In the words of Tony Iwobi, Nigerian in Italy for 38 years, who heads the Northern League's deparment of Security and Immigration, "Ten thousand fake refugees arriving in just a few days -- our president Matteo Salvini is right once more. The Partito Democratico has transformed Italy into an immense refugee camp, with a trite litany that Europe is going to help us, but in fact does not give a damn. Basta! [Enough.] What is needed is a popular revolt to get rid of this government, even using rough methods." Iwobe was among those demonstrating against Operation Mare Nostrum in Milan in October 2104.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.