Review. Casa Nostra: A Home in Sicily

Lurking in the Anglo-Saxon breast is a suspicion ofinferiority, a sneaking hunch that Latin Europeans possessa secret of living well that has escaped the Northerner. It goes beyond a belief that the sea and land of Mediterranean Europe are splendid, the food seductive, and history’s artifacts noble. It encompasses the conviction that the Latin European has a relationship to his surroundings that overcomes routine and inhibition to attain a special inebriation with life itself and special skills in managing both the inebriation and the life.

Thus a considerable trickle of, especially, Englishmen and Americans has sought to plunge into this Eden and hope for at least a partial transformation into Frenchmen, Italians, or Greeks. They find a tree branch in the Midi or Tuscany and try, in the process of nesting, to discover that famous secret of living, by osmosis, by avid learning, even by buying it. (Disappointment is rife, from Umbrian farm houses re-sold at a loss to Zorba’s “splendiferous” demolishing of his young Englishmen’s commercial hopes.) Viewing themselves as intrepid in taking this plunge, they don’t do it quietly, but try to be sure that family, friends, and the larger world appreciate their daring and envy their success, if there is any success.

The result has been a cottage (literally) industry of books describing the building of a house in the South of France, the conversion of a stables in Tuscany, the effort to become a home-owning villager on the Peloponnese. Determined to entertain us, the authors haul out for display (and, we suspect, largely manufacture) an army of thieving realtors, madcap plumbers, heart-of-gold neighbors, and wildly eccentric gardeners. The anecdotes are neat, colorful, and not always very credible. The heart of the place rarely seems exposed. The outsiders appear to remain outsiders, and seek to tell us tall tales only because we are even further outside.

But now, finally, we have the real thing.

Caroline Seller, as she was then, a peripatetic young Englishwoman of impressive backbone and literary talent, truly entered the world of western Sicily by marrying one of three sons of an important, but no longer wealthy, family in Mazara del Vallo, on the far western tip of the island. After their father’s death and their mother’s failed attempt to find prosperity in wine-making, the sons are faced with shared responsibility for a magnificently romantic villa that is so near collapse that only small parts of it are habitable. Each of the sons had gone their own way in life and they had quite different ideas about whether the villa can be kept and saved, even whether any of them want to live there.

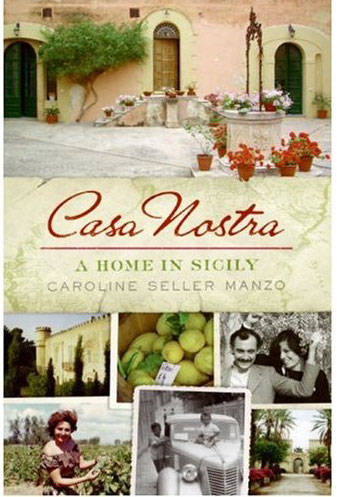

Sitting atop the villa (since the ground floor is in ruins) and atop the book is the author’s mother-in-law, a personaggio no reader will forget, far larger than life but, like everything else in this precise account, absolutely credible. The first woman to drive a car in the town, posing (Harper Collins treats us to the kind of edition the book deserves, with invaluable photos.) as a glamour queen, a young black shirt for Mussolini, the proud boss of the ill-fated winery, and the only woman regularly to burst into the men’s circolo in town, Maria is a matriarch in the grand style. But, more to the point for her alarmed British daughter-in-law, she is the mistress of avvicinarsi, the wizard of stare insieme. Not being able to tolerate being alone for a minute, her schedule of visits, the receiving of visits, shopping, entertaining, and pulling people together seems based, initially, on a belief that everyone feels as she does about being alone.

For Caroline Seller Manzo, this is initially a trial equal to any of the daunting challenges of rehabilitating the villa. She poignantly analyzes the difference between the Englishman’s need for a little privacy (a word with no Italian equivalent), and the Sicilian failure to find such a need as anything but demented. Unlike the slim entertainments served up by other Northern adventurers, this book covers a full generation of living, to wonderful effect. Thus one notices (the author does not need to call attention to it) that the second half of the book is full of parties and dinners, exhausting in their size (a dinner of fifty seems intime) and improvisation, but the complaints of the author have died out. She has clearly achieved what all the “hey-look-at-me” writers failed to do: she has become, not a Sicilian, but a woman at one with sicilitudine. And she has managed, through an exacting accumulation of non-romanticized details, to bring us a long way with her.

Manzo’s tolerant good humor carries through scenes not to be found in the other books. The description of her arrival in Mazara is touching. Tired, possessing very limited Italian, she is unable to respond decently to the warm reception she receives, and is uncertain about the meaning of that reception. Marcello, her future husband, has not come with her and she realizes that she has no idea what his letters have told his family. Is she a casual friend, the clearly-proclaimed future wife, or a woman whose romantic relation to Marcello is as vague as her future relation to the family

A generation later, she is striving to smooth the way for her own daughters to find their accommodation to the worlds their mother has bridged.

Of course, there is food. Anyone searching for the right tomato for the grand August salsa-making, or seeking keys to Sicilian pasta will carry this book the way Henry Adams is carried to Chartres. And there is sun, described by an author with the heart of a 19th century romantic and the skin of a modern woman who knows about cancer. And, of course, there is the Mafia (this is the western tip of Sicilty). The family had had its own brush with that dark side of the island, but not enough for this reader to retain his initial belief that the title was a play on words.

Unlike all her compeers, Caroline Sellers Manzo never asks us to admire her. But, at the end, what the matriarch Maria accomplished and what this willful Englishwoman accomplished must be weighed the way one weighs the importance of Mrs. Dalloway. Certain crucial people bring others together, help save both Sicilian villas and the well-being of those around them, and bring joy to us observers. Her triumph is the triumph of sicilitudine, but it is also her own.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.