Padre Pio Through the Looking Glass

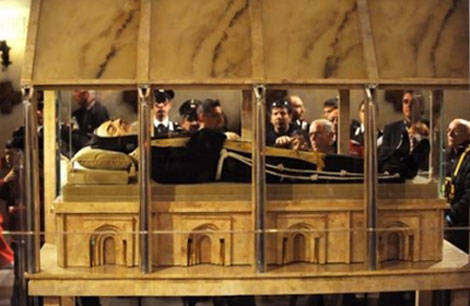

In Italy you’ll see Padre Pio everywhere—in a back-alley shrine, the window of a restaurant, the cover of a cheap women’s magazine, in wallet-size amulet form. His image seems inescapable, but for devotees of the man who is believed to have performed thousands of miracles in his lifetime, now there is the chance to see him in the flesh. At San Giovanni Rotondo, a small town in Puglia whose friary is where Padre Pio spent most of his life, the body of the saint is on display. A mass held last Thursday marked the occasion and was intended to seat some 10, 000 people, surrounding the glass-encased body.

It is almost difficult to qualify the devotion and popularity of the figure of Padre Pio. He is especially revered in southern Italy but for nearly his entire religious career as a Capuchin monk, until his death in 1968 at the age of 81, he was shunned by Catholic officials and the Vatican. Wor d of his miracles unsettled the Church and they often charged him with being a “psychopath” and a fraud. He is said to have had the wounds of the stigmata in his palms, healing, bi-location (the ability to be at two places at once) and levitation powers. John Paul II was the first Pope to believe in his gifts (apparently he was the recipient of a bona fide Pio miracle himself) and was the driving force behind Padre Pio’s canonization in 2002. During his lifetime, the now Saint Pio of Pietrelcina used his mass appeal and popular support to open what was once one of southern Italy’s biggest hospitals. His doctrine of spiritual growth (which includes meditation and examination of conscience) and of the inseparability of God and suffering, has also helped to create an enduring legacy.

d of his miracles unsettled the Church and they often charged him with being a “psychopath” and a fraud. He is said to have had the wounds of the stigmata in his palms, healing, bi-location (the ability to be at two places at once) and levitation powers. John Paul II was the first Pope to believe in his gifts (apparently he was the recipient of a bona fide Pio miracle himself) and was the driving force behind Padre Pio’s canonization in 2002. During his lifetime, the now Saint Pio of Pietrelcina used his mass appeal and popular support to open what was once one of southern Italy’s biggest hospitals. His doctrine of spiritual growth (which includes meditation and examination of conscience) and of the inseparability of God and suffering, has also helped to create an enduring legacy.

An estimated 750, 000 people have made reservations to visit the body of Padre Pio. In the past, the town of San Giovanni Rotondo had already benefited from Padre Pio, receiving ne arly one million visitors a year to his shrine, and as a result, millions of euros for its local economy. Despite criticism for this blatant commercialization, especially from the prominent Bishop of Como and other individuals within the Church, administrators for the region of Puglia see the viewing of the saint’s body as an opportunity to bring more tourists, not only to the monastery town, but to the entire region. Relative to the rest of Italy, Puglia thinks of itself as somewht overlooked by tourists and it relies on the glorification of its native monk—along with sales of Pio-related merchandise, from key chains and plates to religious paraphernalia—to work up an economic stimulus.

arly one million visitors a year to his shrine, and as a result, millions of euros for its local economy. Despite criticism for this blatant commercialization, especially from the prominent Bishop of Como and other individuals within the Church, administrators for the region of Puglia see the viewing of the saint’s body as an opportunity to bring more tourists, not only to the monastery town, but to the entire region. Relative to the rest of Italy, Puglia thinks of itself as somewht overlooked by tourists and it relies on the glorification of its native monk—along with sales of Pio-related merchandise, from key chains and plates to religious paraphernalia—to work up an economic stimulus.

Saint Pio’s body will remain in a glass coffin until September 2009. His face has been replaced with a lifelike wax imitation, commissioned from a company in London that has worked with Madame Tussaud’s, and he is laid in his signature monk’s habit. To the flocks peering through the glass, the saint’s legendary hands may be his most authentic parts. It remains to be seen if some famous Padre Pio devotees, like Sophia Loren or Irish soccer player Damien Duff (it’s said he played with a relic of the saint in one of his shoes), will someday be among the pilgrims.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.