Those Lies about Italy’s Unification

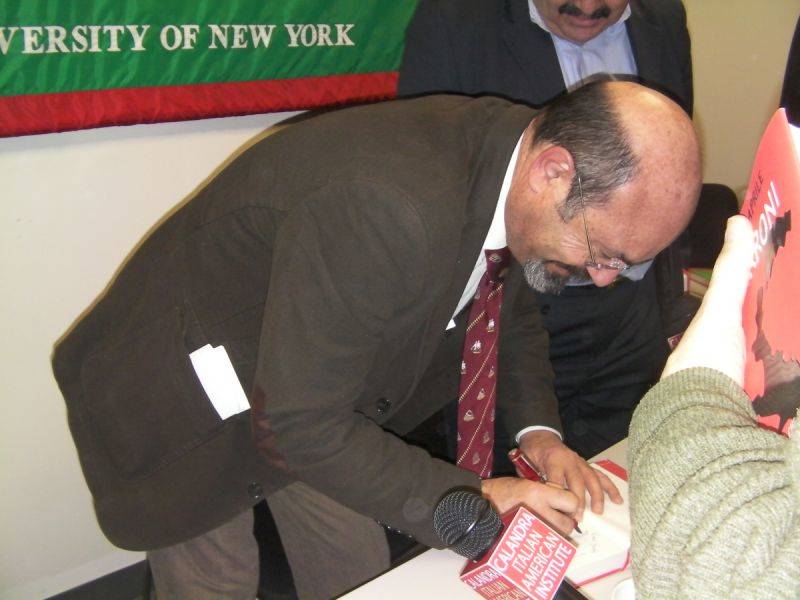

Tell us how the idea of writing Terroni: Everything that was done so that the Italians of the South could become “Southerners” was born. How much research was involved?

I had always believed the history books. But something was wrong because, if the Southerners were supposedly poor, backward, and oppressed, once they were liberated, modernized, and improved instead of being glad they fought it with weapons in hand? Were there really all those bandits in the South? And why, when the response to those weapons was a lost battle, rather than enjoying the “paradise of imports” did millions of people leave when practically no one emigrated before? The more answers I found, the more the questions grew. I started writing but without the intention of carving out a book (it should have been my first but it turned out to be my eighth). After thirty years, during which, fortunately, I accomplished other things…Terroni was born.

The history of the Risorgimento should be rewritten, in your opinion. So we are living a lie…. Can you tell us more?

Every nation of people, every state, every large company needs its founding myths – concise and slightly dishonest fairy tales that are easily told and retold. What do we say about William Tell, El Cid Campeador, and Roland, the paladin of France? Let’s include Garibaldi and the fable of a thousand idealists who alone defeated a kingdom of nine million people, an army of one hundred thousand men. Then let’s compare how things really went: a historical juncture of enthusiasm and interest that gave Piedmont the opportunity to expand beyond measure in the name of the unification of Italy and put its hands in the coffers of various states that prior to unification were gradually being annexed. Italy was made; even the United States, Japan, were unified through wars and massacres. Afterwards, however, both heroes and those on the opposing side gained equal footing in the history books and in the collective memory of the nation. In Italy, the South continues to be vilified, first as justification for the invasion, and today as justification for discrimination: less money, fewer roads, fewer railroads, fewer airports, less opportunity, less power, less respect.

Your book immediately elicits a strong emotional response from either side. I guess your intent was to inspire those who read your book to reconsider and reflect. Can you recommend a particular method?

Having finished the book, I wondered why far more valuable works by greats like Salvemini, Dorso, and many others, had not produced the results that, not only in my opinion, deserved it. I told myself that perhaps they were overly concerned with demonstrating the objectivity of an academic (even if a few, such as Salvemini, were endowed with great irony and humor). So I decided to include my feelings as well – the painful surprise, anger, the sense of having been betrayed. And I realized that I reacted as a reader of my book would. This has made me one of them.

Terroni has enjoyed great commercial success and sparked a heated debate in Italy. It’s now been translated into English. What do you expect from Americans, especially Italian-American readers? Have you received any feedback?

I will recount this episode: I read a review of my book by an Italian-American (I learned later that he works with NATO in Bagnoli). It was a thought out and very well-written article, beyond the flattering things he said about Terroni. I wrote the author to thank him. He replied that he should be the one to thank me because he finally figured out why, despite having the surname Quattrone, he, like his father, was born in New York, but in Italy he is considered an immigrant.

Don’t you think that Southern pride is likely to create an anti-Northern League – in short, a new Southern League?

Absolutely not. The Northern League is a racist party (but it doesn’t mean that all those who voted for it in good faith are also racist). It has invented an identity and a homeland, Padania, which never existed before, to continue to demand privileges for one part of the country to the detriment of the most disadvantaged part. The South calls for fairness and equal treatment, and this applies to any area of the country where there aren’t the same possibilities to travel, study, access medical care, and turn resources into opportunities for development.

Let’s focus on your historical discourse. How important is the message of your book to young people?

Knowing how our country was really born is the first step in destroying the prejudices that divide it. The truth unites. Today’s young people, paradoxically, know the rest of the world (through communication, the internet, social networking, easy and economical travel, Europe without borders and with a common unit of currency) better than their own country – even though they think they already know everything they need to. Looking at their own country with the wonder of a foreigner, they can rediscover it: the recovery of a betrayed memory leaves them curious to know more.

Today, the distance between the North and South is increasingly exacerbated by the economic crisis and clearly not only in our country. What is particular about the situation in Italy?

Whatever period in human history we care to consider, Italy has always been present at the highest level from prehistory to history (Etruscans, Greeks, Phoenicians, Romans, mixing of populations during the Barbarian invasions, the Renaissance, etc.). And again today, Italy is one of the top ten countries in the world. To give you a better idea: Mesopotamia was great and then it was gone. Egypt was even greater and then it was gone. Greece was immense and then it disappeared. Italy was always there. With the Risorgimento, Italy resorted to the creation of an internal colony, the South, to launch its industrial development in the North and pursue the European countries that were already far ahead (Great Britain, France) until we caught up to them. The North–South divide has been and still is used for the same purpose. Our country is the representation and synthesis of the world. Former colonies or countries subjugated by force or economy have liberated themselves and gained momentum (China, India, Brazil, Poland), recovering an awareness of their right to be on par with other players on the world stage. Re-appropriating our own history can lead to the same result in Italy. I mean Italy, not just the South.

During your very successful presentation at the Calandra Institute, among many other things you said: “Italy was born in blood. Even the U.S. was born in blood. All countries are born in blood. We, too, every one of us is born in blood, our mother’s blood. But then we were bathed, fed, cuddled, nurtured…we became part of the family. But the South was born in blood and has never become family.” Perhaps you can start from this comparison in order for us to understand. Why has Italy’s historical path been so different from America’s?

I don’t think I’m capable of explaining it. But you can’t help but notice that the United States was born from an encounter with (and a battle over) remnants of peoples and cultures that took place over a very short period of time and began, in a sense, from scratch. By contrast, the accumulation of millennia and many ideas has weighed on Italy. And when the ideas, the possibilities are too numerous, only one major, shared intelligence can organize them into one unified design or one frightening, violent act, which then must be justified by blaming the vanquished. I believe that Italy has not had all of the intelligence needed at the right time. Recognizing this, it can be fixed. Last August 14, on the anniversary of the massacre at Pontelandolfo and Casalduni (where one thousand riflemen with the right to rape and pillage wiped out two towns with 5,000 and 3,000 inhabitants in retaliation), in his message President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano apologized for the massacre on behalf of the country. It was an important step, the most difficult, to begin the journey of a thousand miles.

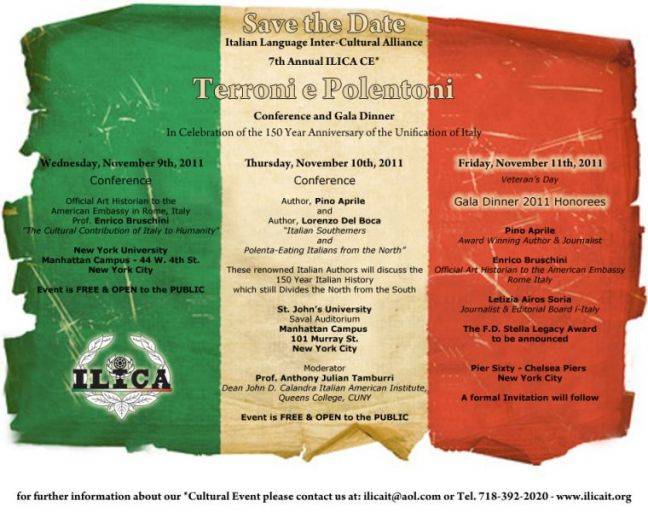

To learn more and meet the authors

Terroni e Polentoni

Pino Aprile and Lorenzo Del Boca

Thursday, November 10, 2011

2:00–7:00 p.m.

St. John’s University – Manhattan Campus

101 Murray Street

Saval Auditorium

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.