Travels in Molise: Splendors of the Samnites and their Scions

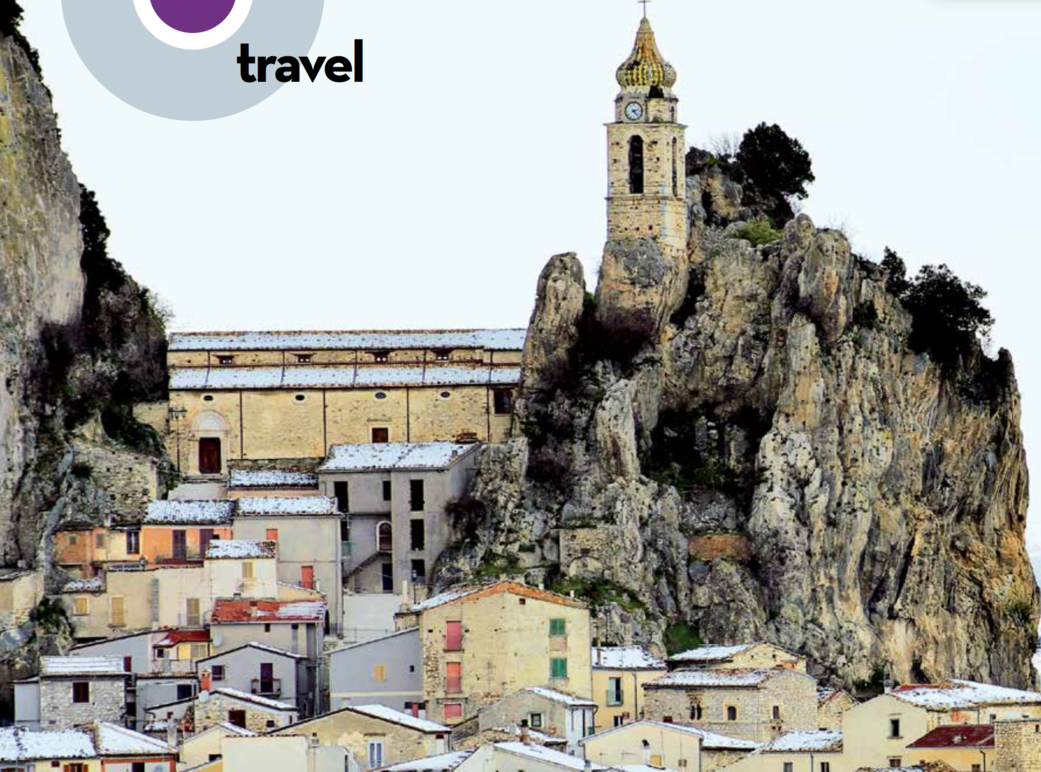

On a brightly lit day at the end of the Summer, we depart L’Aquila and head to Molise, the smallest region in Italy after Val d’Aosta. We’re on the old Via degli Abruzzi, a road that has connected Florence to Naples since the Middle Ages and cuts through Perugia, L’Aquila, Sulmona, Isernia and Capua. Framing the view are the shiny snowcapped mountain peaks of Gran Sasso, Sirente, and Maiella. Abruzzo’s awesome mountains never cease to amaze. After Sulmona the road snakes it way to the Altopiano delle Cinquemiglia, or the Five-Mile Plateau. A vast green plain and clusters of foliage flank the road to Roccaraso. Then the road dips down to Castel di Sangro, the last city in Abruzzo, before entering Molise, a region rich in history, full of mountain- and hilltop towns that look like nativity scenes, hermitages and monasteries, and vestiges of the ancient world.

Back to the Roman ages

About twenty miles of staggeringly beautiful scenery and we’re in Isernia. The city’s historic center is spread over a rocky spur between two valleys where creeks flow downhill and merge with the River Volturno. It’s an old city in the territory once inhabited by the Pentri, a brave tribe that went to war with Rome three times. The heart of the city is Piazza Celestino V and the amazing 14th-century Fraterna Fountain. The fountain is like a magnificent loggia, with columns and capitals. The Cathedral and the Church of St. Mary of the Assumption are worth seeing, as is the city museum, which houses sculptures and inscribed tombstones from the Samnite and Roman ages, as well as artifacts from the Paleolithic Age discovered in nearby archaeological sites. Their rich diet is dominated by pork, lamb and goat meat, as well as beans, handmade pasta, and soups made with local produce. Pentro d’Isernia is an excellent wine that rivals both red and white Biferno wines.

We leave the capital of the province for Venafro, an enchanting city in the Volturno Valley on Molise’s western border. This ancient Samnite city, later Roman, also has a wide variety of interesting items in its cathedral, a Roman edifice with Gothic touches. Its apse was built with stones from the nearby Roman theater. The frescoes inside the temple are well conserved. Also worth a visit are the Pandone Castle, the medieval tower, the churches, and Verlasce, an elliptical structure that was part of the ancient amphitheater—all of which jut out from the walled city. Venafrum was once a pleasant resort town mentioned by Cicero, Pliny and Horace.

Heading to Campobasso

We head back out, this time for Campobasso, but not before making a pitstop in Bojano, a city on the slopes of the Matese Mountains. The origins of Bovianum are legendary. According to the myth of the Ver Sacrum, it was founded in 7 B.C. when a bull leading the cross-migration of the Sabines stopped here and gave birth to the people who would become the Samnites. This myth has given way to a popular and charming reenactment. In 290 B.C. it was the site of the bloody final battle that led the Roman army, commanded by Manius Curius Dentatus, to finally defeat the Samnites in the third war against the proud Italic people. Bojano’s impressive cathedral was built in 1080. Its stone façade has an eye-catching 12th-century portal and rose window. Nearby is the Church of St. Erasmus, which has a magnificent Gothic portal and three mullioned windows. In the chapel hang coats of arms and stone artifacts from the Roman Era and Late Middle Ages.

Other churches from various time periods and family palaces dot this city by the springs of the Biferno River. About twelve miles from Bojano, Saepinum—near today’s Sepino— is an archaeological site that merits a visit. The quadrangular site contains fragments of the Roman city walls, reinforced by circular towers, which date back to the age of Augustus. Just before the walls, where the city’s four main gates stand open, there is a theater, while in the forum there are a few public buildings and a basilica, which still has an arcade. Beyond the walls is the necropolis and the mausoleum of Ennio Marso.

Next up: Campobasso, the capital of the region, perched high up on a hill. This isn’t the time of year to enjoy its most amazing tradition, the procession of the Mysteries during the Feast of Corpus Domini, when sacred tableaux vivant parade through the city—that is the day to really appreciate Campobasso. The modern city sits on the low-lying area, while on the hill dominated by Castello Monforte is the old city, probably of Lombardian origin. It is distinguished by its tangle of roads and narrow steps that climb the hill, where the impressive fortress protrudes from the crenellated walls and angular defensive towers rebuilt in the mid 15th century. It’s really a pleasure to wander the old city’s fretwork of streets and take in the one-of-a-kind architecture. You’ll see the 13th century Church of Saint George, with its bell tower, mullioned windows and 14th century frescoes; as well as Saint Bartholomew and its gorgeous portal. Also interesting is the Church of Saint Antonio Abate, with its precious wooden altars and paintings by Francesco Guarino, a major 17th century Neapolitan painter.

Don’t miss a visit to the creche museum which houses miniature creches from Italy and around the world. The oldest dates back to the 18th century. One thing to point out is the manufacture of knives, scissors and accessories, a real art form practiced at its best in Campobasso and, in the province of Isernia, Frosolone.

Climbing down to the sea

With Campobasso at our backs, we climb down toward the sea. The road wends through a group of hills crowned with already-budding olive trees. They produce excellent oil here. Halfway to the Adriatic Coast, we stop in Larino, a bucolic town with captivating glimpses of the medieval world and ruins of the Roman city Larinum, including an amphitheater from the 2nd century A.D. and a villa where three gorgeous mosaics on display in the Doge’s Palace come from. At the end of May, to celebrate Saint Pardo, hundreds of ox-driven carts covered with flowers and embroidered drapes race through the streets of Larino. Later in the evening, under torchlight, ancient pastoral “carrese” songs are sung. Not far south of here is Ururi, a village that has been inhabited by an ancient Albanian colony for centuries. For half a millennium, this bona fide cultural enclave has jealously guarded the language, customs, and religious rituals of Albania, a country they left fleeing persecution from the Turks.

A little farther down the road is Termoli, a pretty seaside city with a large port where ferries depart for the Tremiti Islands. The elegant historic center sits on a rocky promontory overlooking the port, beaches, and coves. Also facing the sea is the splendid 12th century cathedral, among the most beautiful examples of Roman architecture in the region. Decorated with pilasters, arcades, and mullioned windows, the church also has a magnificent main door. Beautiful too are the apse and sidewall, and the interior and crypt are noteworthy. A little way’s off is the castle, a truncated pyramid topped with a tower. The whole promontory is fortified by robust walls built by Frederick II to defend the port and the city. The orderly, green, new part of the city lies above the historical center. Not far from the beach, in a deconsecrated church, is the civic gallery, which houses contemporary art and puts on figurative art exhibitions.

From Termoli, we follow the Adriatic Highway all the way to San Salvo, then climb the valley of the Trigno River that flows down from the Apennines. Even in winter, the valley is ablaze with different colors. The river breeds vegetation that during the warmer months turns luxuriant. We climb back up the southern crag of the valley to Trivento, the episcopal seat back in 1000 A.D. Dedicated to Saints Celso, Nazario, and Vittore, the cathedral was built over the ruins of a temple to Diana. In one of the beautiful small naves of the Paleochristian crypt is the sepulcher of Saint Castro with a bas-relief depicting the Holy Trinity framed by dolphins. There is an interesting doge castle and a long spiral staircase that leads to the cathedral square.

The ancient Samnite city of Trivento became the Roman municipality Terventum in the 1st century B.C. Roman country houses that produced oil and wine have been discovered in the vicinity. We have another stop to make—Agnone. As we travel back up the valley, we see signs for San Angelo Limosano. We don’t have time to turn off, but it’s worth mentioning that in 1209 Pietro Angelerio was born there. On August 29, 1294, the Benedictine monk became Pope Celestine V in the basilica of Santa Maria di Collemaggio in L’Aquila. According to historical accounts, 200,000 pilgrims attended the coronation. Like Francis of Assisi and Gioacchino da Fiore, he was an important spiritual figure of his time, revolutionizing the church by instituting the first Christian jubilee and resigning five months after his election. An act that Benedict XVI would repeat in 2013.

Agnone and its campane

Finally we arrive in Agnone, a magnificent little city with Samnite origins known for its thousand-year old bell manufacturing trade—its bells toll in half the world—and for goldsmithing. The famous Campane Marinelli, which has been in business for, as we said, a thousand years, is one of a handful of foundries that has the privilege of using the papal coat of arms. Among the city’s wonderful monuments are the Parish of Saint Francis, with its Gothic door topped with a rose window, and the churches of Saint Emidio, Saint Antonio Abate, Saint Amico, Saint Nicola, Saint Peter, Santia Maria di Majella, and Santa Croce.

More churches sit outside the walls. It has other architectural gems, including family palaces and an Italian-Argentine theater built in the first half of the 1900s with donations from the people of Agnone who emigrated to South America. Agnone’s famous ciocavallo and scamorza are examples of the long cheesemaking tradition in Molise, which boasts a wide array of cow and sheep milk cheeses. It also produces excellent pasta, oil, fine wines, cold cuts and truffles. Our trip ends in Pietrabbondante (“Stones in Abundance”), a charming village which we’ll not say too much about; the name itself gives you a sense of all the wonders and flavors of Molise, a land full of curiosities to unearth without needlessly hurrying along.

—

* Writer and journalist Goffredo Palmerini continues his fascinating journey through the beauty of Italy.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.