Puccini’s 100-Year-Old Girl

Decades before director Sergio Leone, with the fundamental aid of Clint Eastwood and Ennio Morricone, created a new western genre, made in Italy, commonly known as Spaghetti Western, there was Puccini's opera La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West). On December 10, 1910, the Metropolitan Opera gave its world premiere, a huge event that involved the greatest operatic names of the day, such as Arturo Toscanini and Enrico Caruso. It marked the first time that an Italian opera was premiered in America and both the attention of the New York public and the price of tickets reached unprecedented levels.

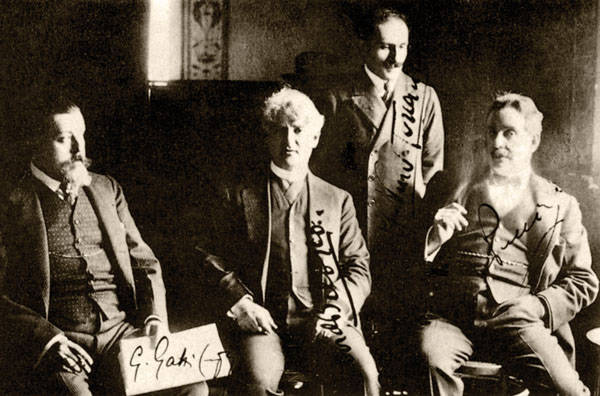

One hundred years later, the Met commemorates this event by reprising the opera, in a Giancarlo Del Monaco production from 1991, starring Marcello Giordani, Deborah Voigt, and Lucio Gallo, and conducted by Nicola Luisotti. For the occasion, the Italian Cultural Institute organized an event coordinated by Prof. Deborah Burton of Boston University, which included the grandchildren of Toscanini and Puccini, musicologist Allan Atlas, music historian Harvey Sachs, as well as Giordani and Luisotti. Del Monaco himself and baritone Lucio Gallo were also present, but as spectators.

The panel was introduced first by the director of the Italian Cultural Institute, Riccardo Viale, who

expressed the importance of this 100th anniversary, simultaneous with the 150th anniversary of Italy's unification. Born in 1858, Puccini lived through the first six decades of his unified homeland, and died, in 1924, during the first phases of the Fascist regime.

After Viale, the podium was taken by Italian Consul General Francesco Maria Talò who suggested that this event was a turning point in the relationship between Italy and New York, the repercussions of which are still felt today, one hundred years later.

Next it was the turn of Sarah Billinghurst, Assistant Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who explained some of the lesser known stories behind this work - for instance, the fact that Fanciulla was not commissioned by the Met, and that New York's famous opera theater was chosen as part of a bargain with the Ricordi publishing house in exchange for performing the composer's early opera Manon Lescaut in Paris (for the first time) during a tour of the

New York company; also, that Puccini was paid 20,000 Lire (“about 11 euros” joked Del Monaco from his seat) for composing the opera. Actually, if any such comparison is possible, the sum would round off to almost $120,000 of today.

Ms. Billinghurst explained that although the opera was a huge success (there were 19 curtain calls on opening night), the Met only reprised it ten times during its first century. On the other hand, it was the first opera to be performed in the new Met, when it was built in 1966 (during a student matinée; the actual first opera was Barber's Antony and Cleopatra) and this current centennial production will be broadcast live in HD in 46 countries around the world, although sadly not in Italy, which apparently remains technologically impaired.

Finally, the reins were handed to the panel, led by Prof. Burton, the mind and motor behind these centennial celebrations and their relative website, www.fanciulla100.org. After delighting the audience with a 1910 film of Puccini in America (audio and video from two different sources) and a tour of the website and its multimedia treasures, she handed the floor to music historian and Toscanini biographer Harvey Sachs, who moderated a mini-conversation between Walfredo Toscanini and Simonetta Puccini, the grandchildren of the two operatic titans. They elaborated mainly on the relationship between the two artists, and Mr. Toscanini explained that his grandfather referred to Fanciulla as a “symphonic poem”, with the orchestra as protagonist - a view shared by Giordani and Luisotti. Also, Toscanini had made a lot of changes in the actual score while preparing the orchestra, while Puccini was still in Italy. Sachs pointed out that this was not uncommon and that both artists represented an approach typical of their day to the preparation and performance of operas.

Allan Atlas spoke about the very close relationship between David Belasco's original play and Fanciulla's libretto and punched holes in the myth of Puccini's using a piece from that play as the

Minstrel's song. Actually, he explained, Puccini didn't write the theme himself, but it came from a 1904 publication of a Zuni Indian melody, transcribed by Puccini’s friend Sybil Seligman from what was originally a chorus of virgin maidens, arranged by Carlos Troyer. But the real treat was Atlas showing excerpts of the Puccini manuscripts in the various stages of composition, from the early sloppy motive sketches to the more continuous – but still sloppy – successive drafts.

Next, it was the turn of the panel's two artists. Luisotti spoke about the first time he performed Fanciulla as a chorus member in Lucca in 1985, which marked the current production as his own personal 25th anniversary. He also confessed how scary it is to conduct this score, which he considers to be the hardest Puccini opera – a work that can create many difficulties for the conductor. Giordani, on the other hand, is singing his first Fanciulla, and he explained that the role of Dick Johnson is exotic, especially if one is more used to the traditional single-faceted roles of Cavaradossi or Rodolfo. “DJ”, as he calls him, is part of a different culture – for Puccini, but also for the other characters in the opera – and expresses his latino romantic and passionate side within the rough traditional western good guy/bad guy double-sided role.

The public listened carefully to all of these points of view and interacted with the panel, asking questions about the music but also about the issues and legends that surround this opera, such as Andrew Lloyd Webber's supposed plagiarism of Fanciulla in writing his famous Phantom of the Opera and the many stories of Toscanini in rehearsal. Del Monaco took part in the debate as well and explained his personal love for Puccini derived from what he calls his “cinematographic style”, not to be confused with a “movie composer”.

At the end of the Q&A, Prof. Burton thanked everyone present and – with a slight alteration to the libretto’s “Whiskey per tutti!” – announced, “Vino per tutti!”.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.