Olnick Spanu, Pioneers of Italian Contemporary Art

Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu founded Magazzino – which means warehouse in Italian – in 2017 in Cold Spring, New York, where a computer factory once stood.

Surrounded by nature, the beautiful, airy space showcases works by contemporary Italian artists from the mid-1960s onwards.

Currently on view is an impressive, state-of-the-art selection of Arte Povera, a crucial Italian contemporary art movement that remained until recently virtually unknown in the United States.

“Our collection does not only focus on Arte Povera,” Spanu insists on specifying right from the start, “it is focused on post-war Italian art from the early 1960s to contemporary artists today.”

“Arte Povera is an important segment of that,” he concedes. And it’s what is currently on view at Magazzino, though it is not what he and Nancy originally intended when they began collecting. “We always knew that we wanted to divulge Italian art abroad,” he explains, “but we came across Arte Povera almost accidentally.”

His and Nancy’s first encounter with the movement came in the 90s during a visit to Castello di Rivoli, a contemporary art museum outside of Turin, following the suggestion by their friend and gallery owner Sauro Bocchi. “We wanted to learn about contemporary Italian artists and he suggested we start from there.”

And that’s when their love for Arte Povera was born. They were immediately struck by this incredibly avant-garde movement of which they previously knew very little and began adding it to their collection, which at the time included an exceptional selection of Murano glassworks as well as a body of Italian ceramics (by Guido Gambone, Marcello Fantoni, Gio Ponti, Fausto Melotti, etc.) among other things.

“I don’t like the term collector,” Spanu explains, “right from the start, the idea was to share art with others.” They started talking about it with their friends and eventually founded the Olnick Spanu Art Program.

The program began in 2003, when their friend and artist Giorgio Vigna visited them in their country property in Garrison, New York. Vigna and his wife were “trapped” there by a power outage and during his permanence the artist noticed a water cistern covered in cement, which he thought would make a wonderful pedestal. He then drew up a project based on the design of a ring he had previously made for Nancy. They loved it and commissioned him to create it.

The work, entitled La Radura, was then built in Italy, shipped to the US and they all installed it together on its pedestal.

This experience inspired them to create a program and have one artist come each year to produce site-specific works around the property. They saw it as a way to support Italian artists, give them a space to create and an opportunity to work in the United States.

“We wanted to support artists we thought were great but we could only manage to host one each year,” Giorgio says, “so we put a lot of effort into choosing the artist, by visiting galleries, fairs, studios across Italy.”

After Giorgio Vigna came Massimo Bartolini, Mario Airò, Domenico Bianchi, Remo Salvadori, Stefano Arienti, Bruna Esposito, Marco Bagnoli, Francesco Arena, and Paolo Canevari. And for each one, the entire process, from the idea to the realization and installation of the work is beautifully illustrated in sleek and handy catalogs.

Meanwhile, all their collections were growing. The Murano glass one for example, which they began to exhibit across the world in shows designed by famed designer and Nancy and Giorgio’s good friend, Massimo Vignelli. “Massimo was central in teaching us how to manage our collection, not just physically but also mentally,” Spanu notes. “That’s what started it all.”

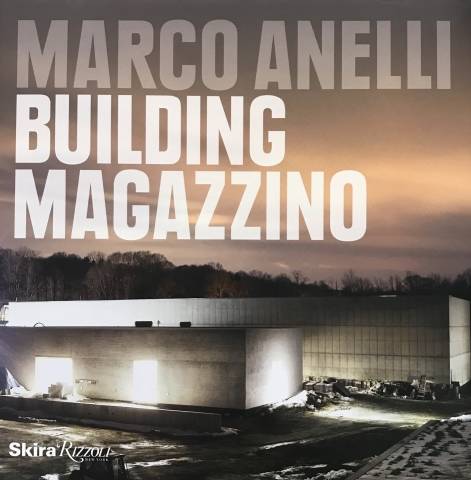

Eventually, they realized that they needed more space, a place to store them, a “magazzino.” They initially wanted to expand their existing property but when that revealed impossible they decided to buy a nearby lot, a former computer factory, and worked with architect Alberto Campo Baeza to develop the plan for Magazzino, which was then designed by Spanish architect Miguel Quismondo, who has been published in la Biennale di Venezia, Architectural Record, A+U, Casabella, and Domus among other publications.

“Our initial intention was to exhibit our collection, not to make an Arte Povera museum.”

Once again, the entire process was documented, this time by photographer Marco Anelli who took countless beautiful shots over the course of 3 years, capturing the evolution of the space, the different stages of construction but also showing the people who helped make this project a reality. He created sticking portraits of everyone involved from builders and gardeners to engineers and architects. “As a sort of tribute to the men who worked tirelessly even in the most strenuous circumstances, under the scorching summer sun and in the brutal winter snow.

Some of these photos were featured in an Arte Povera exhibit curated by Paola Mura and Vittorio Calabrese held this past summer at the Civic Museum of Cagliari in Sardinia. “We didn’t just exhibit the works in our collection but thanks to the photos of Marco Anelli also the container of our collection, Magazzino itself.”

Magazzino’s inaugural exhibit in 2017 included many works that had belonged to the collection of Margherita Stein, the founder of the historic Galleria Christian Stein and one of the pioneers of the Arte Povera movement. “We decided to dedicate it to this little-known figure of Italian contemporary art, who has always fascinated both Nancy and me.”

After the show’s incredible success, they realized the resonance of Arte Povera and the importance of showing Arte Povera in the US. Through Magazzino’s fellowship program, they found that important research on the subject was being conducted by young scholars both in Italy and in the United States. “There was a lot interest in this movement - even before we arrived - there maybe just wasn’t the right stage for it yet.”

And soon after the opening of Magazzino, a couple of important Arte Povera shows took place in New York. One of them was curated by Ingvild Goetz at Hauser and Wirth Gallery and another by Germano Celant at Levy Gorvy. Since then, there have been many more across the United States. In May, the Dia Foundation in Beacon will open a show dedicated to one of the movement’s key figures, Mario Merz.

In just a few years, Magazzino has done an incredible job of promoting Arte Povera in the US. And, although Giorgio and Nancy’s main goal has always been to divulge the work of today’s Italian artists, this movement was so important and formative that it is essential to be familiar with it in order to contextualize and understand what comes after. That’s why a rotating selection of their Arte Povera collection will always remain on view alongside a program of varying exhibitions.

“The young artists we support and follow certainly have ties with Arte Povera - Francesco Arena for example doesn’t conceal that he is inspired by artists such as Boetti, Anselmo - so it’s important that we keep exhibiting it.”

Also important is producing documentation, something else that Magazzino excels at. This way the work of these artists continues to exist and spread beyond museum walls and into classrooms, universities, galleries, homes. Beyond publishing English-language catalogs for all their exhibits and projects, they are also beginning to translate key texts into English, starting with Giorgio Verzotti’s publication on Mario Merz.

Furthermore, since terminating the Olnick Spanu art program in 2015, they’ve been carrying out a variety of other initiatives, including a collaboration with New York University’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò: each year they invite an Italian artist to take up an artistic residence in Magazzino, which culminates in an exhibition held entirely at Casa Italiana except for one work, which gets placed outside Magazzino. The first exhibition was on the work of Ornaghi & Prestinari, the second on Alessandro Piangiamore. Last year, it featured the works of Renato Leotta and this year will be the turn of Namsal Siedlecki, an artist of Polish and Italian descent, who studied in Italy and whose works will be on view starting May.

Magazzino also hosts a Scholar-in-Residence. This year's is Dr. Tenley Bick, an art historian specialized in post-war and contemporary Italian art among other things and Assistant Professor of Global Contemporary Art at Florida State University, as well as the first American to hold this position. During her residency, beyond producing research focused on postcoloniality, interventionist practices, and the legacy of countercultural aesthetics in contemporary Italian art, Bick will also contribute to the museum’s educational and public programming by leading special exhibition and museum tours, organizing and participating in the institution’s annual lecture series, and curating a film series dedicated to Italian experimental cinema with Magazzino Director Vittorio Calabrese.

Theyn also collaborate with local entities such as the Dorsky Museum at SUNY New Paltz, where last year's Magazzino Scholar-in-Residence Francesco Guzzetti organized an exhibit titled "Paper Media: Boetti, Calzolari, Kounellis" from the research conducted on Magazzino's own collection. It was the first Arte Povera exhibit of exclusively works on paper ever realized in the US.

Additionally, they work with the Italian Consulate and the Cultural Institute on initiatives such as “Young Italians,” an exhibition inspired by a 1968 show by the same name curated by Alan Solomon to promote the work of talented young Italian artists who were not known in the US at the time, including Kounellis, Pistoletto, Castellani, all of whom are represented in the Olnick Spanu collection.

And they don’t exclusively support Italian artists, but also American ones with ties to Italy, such as New York-based Melissa McGill, whom they helped realize an ambitious public art project titled “Red Regatta” in Venice, which featured 52 red sailboats engaging in choreographed regattas across the laguna.

Such projects show the numerous points of contact between Italian and American art. As will an upcoming exhibition, which will open on June 13th and show the parallels between Boetti and Fontana and the renowned American artist Mel Bochner and more generally the impact that contemporary Italian art had and continues to have on the global art scene.

All these activities carried out by Giorgio, Nancy, and the devoted staff of Magazzino lead by Director Vittorio Calabrese aim to fulfill the mission to advance scholarship and public appreciation of postwar and contemporary Italian art in the United States, advocate for Italian artists by celebrating the range of their creative practice, from Arte Povera to the present day and exploring the impact and enduring resonance of Italian art on a global level.

---

Magazzino Italian Art

2700 Route 9

Cold Spring, NY 10516

+1 (845) 666 7202

+1 (845) 666 7203

[email protected]

Visitor Services and Tours

Victoria Jones

[email protected]

Hours

Monday: 11am – 5pm

Tuesday: Closed

Wednesday: Closed

Thursday: 11am – 5pm

Friday: 11am – 5pm

Saturday: 11am – 5pm

Sunday: 11am – 5pm

Click here to book your free shuttle >>

Admission is free to the public. No reservation required.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.