New Voices on Primo Levi: Andrea Liberovici

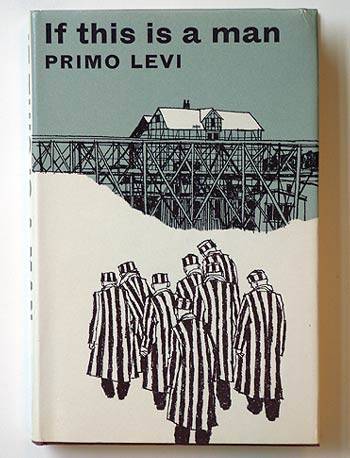

When the books and the tragic life story of Primo Levi started spreading around the world, they had an enormous cultural and psychological impact on everyone’s conscience and on our collective sense of Memory. Primo Levi became one of the most prominent Italian Holocaust survivors after he wrote the book “if This is A Man” (translated in 24 languages) in which he recounted the gruesome details and the gradual loss of humanity of the concentration camps.

Through his works Levi did not only make people of every generation remember and discuss the causes and effects of this tragic historical event, but he also conceptualized the Holocaust by creating images that capture the lowest aspects of humanity’s inhumanity.

The Centro Primo Levi, the Jewish Center of Italian Studies in New York City, has honored the writer in many ways and this year's 4th edition of the International Symposium “New Voices on Primo Levi” focuses on the relation between the “West” and the “Rest”. If most Western countries and institutions are largely familiar with this history, not many people know that, for example, in Korea and Japan, Levi’s works triggered a national reflection upon the effects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s bombings and the discriminations of the Korean minority.

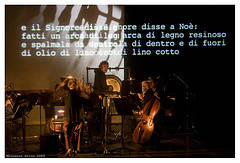

Opening the Symposium, on October 26th at 8:00 PM (Asia Society, 725 Park Avenue) is Andrea Liberovici’s The Transparency of the Word, Cantata for Primo Levi.

Andrea Liberovici is an acclaimed mutlti-media artist, a talented composer, a director, and the founder of the Theatre Company “teatrodelsuono”. He has collaborated with many International artists.

Mr. Liberovici is coming to New York not only for The Transparency of The Word but also for the premiere of another show of his, Mephisto’s Songs. In an interview he kindly explained his approach to his work, the inspiration for both shows, and what Primo Levi's message means to him.

Although the shows seem really different, there is a deep connection to Levi’s honest portrayal of mankind’s fears and inner monsters.

Levi once said that “aims in life are the best defense against death” and it seems that having his words come to life again is a meaningful step towards fighting mankind’s darkest instincts and ultimately death itself.

What led you to re-discover Primo Levi’s work and which of his words inspired you in creating the musical experience La Trasparenza della Parola?

I grew up surrounded by the cultural environment linked to Primo Levi. My father was actually a personal friend of his. Emilio Jona who has written this amazing text for the the concert La Trasparenza della Parola, was also an intimate friend of his. He knew Levi’s works deeply and in his text there are not only different specific quotes but the entire concert is built around nine essential keywords extrapolated from Levi’s novels. He has written short poems around these nine keywords.

My dad -who was also a composer – was commissioned to write the music for this text in 1987, when Primo Levi died, during the first Salone del Libro in Turin. There was a big memorial night for Primo Levi and that’s where the concert had to be performed, but at the time it was almost too big to be considered possible and for budget reasons it didn’t work out. The text was preserved even years after my father passed away, in 1991, and when I met with Emilio a couple of years ago he showed me the text my father had to have composed music for and asked me to take up the project and find new ideas. I looked at it and I liked it a lot, for many reasons. Primo Levi was always in my personal memories: I read him as a young man and I heard people talk about him when I was a kid. When I started to re-read his works for this concert I realized how his analysis of mankind, of its darkness, is timeless and shocking. It was clear to me that this was a classic like Shakespeare, because every time one realizes that he gives an almost scientific x-ray of the human nature that is constantly true: we are at war between us, the absence of human rights and violence hasn’t stopped with World War II. He analyzes incredibly well the deepest and darkest aspects of our souls. He becomes a classic because he writes about the men linked to that massacre and men are still the same and have a mephistophelic side in them.

You performed this show in Turin, Levi’s birthplace. Does the city itself, New York, add a special significance this time?

Well, first of all I’m extremely pleased and honored to be in New York but, for me, in a way, this concert could be performed anywhere in the world and have the same effect, be it in Baghdad or South Africa. This concert is just a little drop in a vast ocean, but the more opportunities we have to talk about the basic rights of humankind, the happier I am. Of course New York is one of the capitals of the world and as I said it is crucial to have Primo Levi’s work discussed here: I wish that Levi was studied in every school in the world. I’m also very grateful that institutions like the Centro Primo Levi exist because of the importance of spreading these words.

All of your works are characterized by a syncretism of media. Do you find yourself comfortable in the definition that was given to you of a “global composer”?

It’s a definition that at first could sound a

little pretentious but truthfully it is what my work is really about. I started as a composer (I studied in a Conservatory) but I also went to a Drama Academy in Genoa, one of the most illustrious in Italy and I always thought - and now even more with new technologies - that all the arts, all media should ultimately converge. New technologies, the ones linked to creativity, are these exciting new instruments that are available to us at the moment. It is as if one created a new piano that could connect notes, images and even sounds that are not necessarily “musical”. There are various artists that brought performance art and the merging of different media to a new level. I think the goal for any artist or anyone who’s interested in communication, in music or in cinema, is to really understand in what time he or she is living, to be in touch with his or her time. When the first piano was created, music changed completely, and new harmonies were possible to be composed because the way of thinking about art and the way we perceived certain things in the world had been revolutionized. And that is why, today, I like to work with images and videos as well.

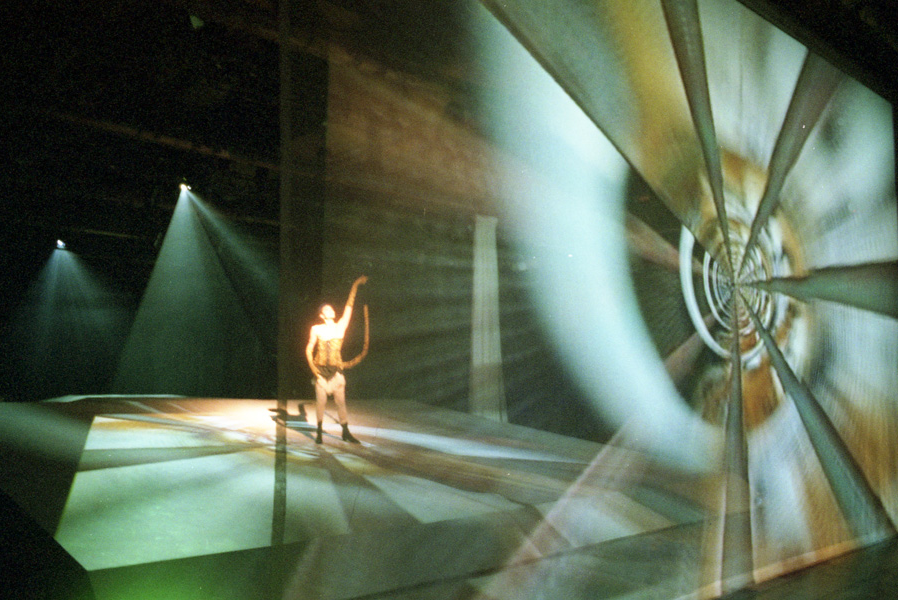

You are also bringing to New York Mephisto’s Songs at the Apollo Theatre. Goethe’s Faust has been interpreted over the centuries in many ways, what is your take on it? Why does it still matter today?

This is a project I have been working on for a long time. I created a show in 2005 with Gassman called Urfaust and it was the first time I approached that text from a dramatic point of view. Urfaust is the version of the “famous” story that Goethe wrote as a young man and it’s more direct and shorter than what then became Faust. This story is a great classic as well and much like Primo Levi perfectly captures the human soul. Faust is someone who in spite of his almost total knowledge, having studied every single subject known to man, from theology to physics and mathematics, still feels as if he is missing something, as if he knows nothing about the world in its essence, about the meaning of life. He signs a pact with the Devil to understand what it means to really be happy. With that in mind, I wondered who is actually really happy in our modern world, a world where we know everything, we depend on information and media, but we still wonder how to pursue happiness. In another of his classics, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship,

he explains that only when we act with the other’s best interest in mind and not our own do our selfish needs shift from wondering 'how am I', to 'how are you' in the deepest sense of the question. Unless there is this shift, this development, when you put this into action, only at that moment will you know yourself. With Urfaust I had the intuition that Faust and Mephistopheles were connected, were in fact two sides of the same person and there is nothing mystical in this idea of the Devil. We constantly act on our self-destroying instincts, instead of just living and being happy here and now, and not in another life. Men of today are not that different from men in Goethe’s age, dominated by wrath, greed, passions, all these “extraordinary illusions”.

And how do the songs reflect these ideas and connect with our modern culture?

After that first experience with Urfaust I composed a series of songs, monologues and videos. Goethe’s Faust, in fact, is actually not a dramatic text like Urfaust is, but it’s a giant novel, an epic one, a collection of popular ballads, as defined by the author himself. If I have to think about popular ballads today I’m inspired by the structure and genre of pop, funk, rhythm n’ blues. I don’t completely conform to these genres, like a more traditional musician would, so the songs are loosely inspired. There are 8 songs that follow an hour of the day of the main character Mephaust: a day filled with love delusions, ambitions, fears, sex and thoughts about the world and all of mankind.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.