Is Marriage the Ultimate Bourgeois Trap?

Anna Lawton:

First of all, congratulations for the American edition of Ties. What was the

reaction of the American public?

Domenico Starnone: Hard to tell. It’s got positive reviews, and the readers I met during my tourin March welcomed me warmly. But this doesn’t mean much. It’s a very “Italian” story, and this may be an obstacle. Although, the painendured during a family crisis, or when a family gets back together without actually overcoming the crisis, can be felt by anyone. In fact, don’t we in Italy, and in the whole world, read very “American” novels? The place where a story is born is extremely important, its specific local features are the salt of the story. To erase them in order to make the story work everywhere would be a terrible mistake. It is essential ways of life different from ours possess a heart, and that in their heart beats we can find our own.

AL:

The title, Ties, seems to be a metaphor that connotes family relations. As such, it creates a certain ambiguity, because the ties can be done and undone, and perhaps redone. How is this ambiguity rendered in the novel?

DS:

The ties figured in the title appear only once in the novel, and they are just shoe ties. When the boy, Sandro, realizes that he is tying his shoes in exactly the same way

his father does, the metaphorical ties—the emotional ones—which had been apparently cut off acquire strength. Aldo, the father, comes back home, the family is reunited. But his return is not a happy one. My idea was that the metaphorical level can be totally disjointed from reality, and that what seems to be a

winner as a metaphor in reality is a flat defeat.

AL:

Besides the ties, there is an other central metaphor which is extremely important, also because of its visual impact. It is the devastated apartment. This image saturates

about two thirds of the novel and it is described in minute details. Why does it occupy so much space?

DS:

It was pointed out to me that most of my stories end up in an apartment. It’s true. Apartments are a rigorously defined space, they give us an impression of order and

safety. But in Ties, the order is only an illusion, and if someone brings chaos to the surface the hidden truth comes up from the bottom. And this does not concern only

apartments. Any kind of order is only a lid over disorder. And if the pot starts boiling, the lid pops off.

AL: There is more than one narrator in this story—one may use the term “polyphonic” to describe it. The narrators are the three main characters, and the reader follows

the individual point of view of each as they define ourselves and the other two. Part one is narrated by Vanda, the wife, through the letters that she wrote to her husband. Part two is narrated by the husband. And part three, by their daughter Anna. Why did you choose this structure?

DS:

I thought it was the only possible structure. I thought of the three parts of the novel as self-contained short stories. Wife, husband, children—although they’re a family

they gradually grew estranged into separate worlds, and each now has his/her own voice which does not communicate with the others. The reader cannot intertwine those three voices—it’s now impossible to connect them—and therefore he makes them clash. The story is resolved in this clash.

AL:

There are some flashbacks to the 1970s and the youth movement that produced the cultural revolution. What is their function in the narrative context?

DS:

The references to the 1960s and 1970s tell of the end of the old patriarchal family and the attempt to create new ways of living

together. But the story of Aldo and Vanda ends up in failure, and shows us that we are still in the middle of the ford. We cannot go back. Just

like in the devastated apartment, where it’s not only impossible to put the shards back together, but it’s even wrong. At the same time, to live amidst the debris generates

suffering, as it happens with the children, Anna and Sandro.

AL:

At one point, Aldo justifies leaving the family in political terms: “Marriage is a bourgeois trap. By leaving you, I’m actually setting you free, you and the children.” This line connotes Aldo as an irresponsible person, but it also broadens the issue to the field of social criticism of marriage as an institution. True?

DS:

Yes. Marriage is a fundamental institution that throughout history has been experienced as an extremely painful necessity. It’s been wildly criticized, but it’s always come back as good as new. It seems we’re not able to figure out other, less trite, ratifications of love which would also ensure mutual assistance.

AL:

In the Nineteenth century and up to Modernism, the novel contained a moral. But then there was a change in literature. The moral became ambiguous, although not

absent, and the reader was forced to make his own conclusions. In your novel, the characters/narrators are not very likeable, and certainly not exemplary. Why did you

make them this way?

DS:

I don’t think a novel must be edifying and the characters likeable. Morals grow old, and what feels upright today it may feel corny tomorrow. Literature has one single task: to tear apart screens, to show what we don’t see or pretend not to see.

AL:

We said that Ties deals with family relationships. In your novels the family is a recurrent theme—first in Via Gemito, then in your latest one, Scherzetto. Why do you

have this continuous interest in the family?

DS:

The family is the place where the individual, as a young animal, receives the first fundamental varnishing that will proudly distinguish him from other forms of life. But it’s also the place where the humanization process shows its cracks. In this sense, it is an extraordinary and inexhaustible narrative space.

AL:

On this precise point, I’d like to broaden the scope of the discussion and place your novels in the context of contemporary Italian literature. The prevalent theme to-

day seems to be the family. Of the twelve books in competition for the Premio Strega, more than half were novels/memoirs, reminiscences of childhood and the family environment on a historical background. Can you comment on this trend?

DS:

Well, the family has always been a central theme, often found in extraordinary novels. Today we should examine each individual novel and see how the family setting is being used. We’ll probably discover an interesting variety of approaches. Therefore, I want to avoid any generalization.

AL:

Thank you so much, Domenico, for sharing your views with our readers. My wish to you is that the American edition of your novel will

help to strengthen your “ties” with the USA.

-----

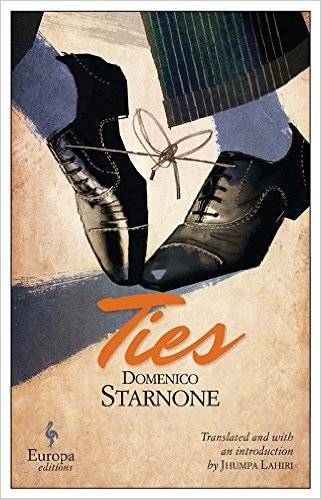

Ties

Domenico Starnone

Translated by Jhumpa Lahiri

Europa Editions, Pages 144

Ties is the thirteenth work of fiction written by bestselling Italian novelist Domenico Starnone. It’s a powerful short novel about relationships, family, love, and the ineluctable consequences of one’s actions. Vanda and Aldo’s marriage, like many others, has been subject to strain, to attrition, to the burden of routine. Yet it has survived intact. Or so things appear. The rupture in their relationship lies years in the past, but if one looks closely enough, the fissures and fault lines are evident: a cracked vase that may shatter at the slightest touch. Or perhaps it has already shattered, and nobody is willing to acknowledge the fact. Known as a consummate stylist and beloved as a talented storyteller, Domenico Starnone is the winner of Italy’s most prestigious literary award The Strega. Ties is powerfully translated by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri.

For more info on the book click here>>

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.