The “Human Capital” into the Ailing Soul of Northern Italy

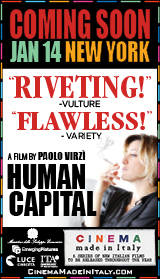

“Il capital umano” (“Human Capital”) based on the novel of the same name by American writer Stephen Amidon, by film director Paolo Virzì is Italy’s official entry in this year’s Academy Awards competition. Virzì, born in Livorno March 1964, is one of Italy’s foremost film directors. He studied at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, in Cinecittà, Rome and was strongly influenced by his reading of classic American literature.

His debut film, “La Bella Vita” (1994), was presented at the Venice Film Festival and won the Ciak d’Oro prize, the Nastro d’Argento award and the prestigious David di Donatello Award in the “Best New Director” category. His later films continued to be recognized for their insightful commentary and critique of Italian society. In 2010, the Italian Film Industry Association selected his “La prima cosa bella” as the country’s official entry for the Academy Awards.

It can’t be a coincidence that a novel originally set in Connecticut can so easily be transposed to northern Italy in 2010. What does this say about contemporary Italy?

In fact it’s not a coincidence. The world has gotten smaller. We all have the same smartphones in our pockets, we’re all living in the same landscape, we’re all dreaming the same dream and suffering the same distress. Of course each person has his or her own characteristics, as an individual but also as a social, political, and aesthetic being. We took the plot from a novel set in Connecticut and breathed into it the ailing soul of northern Italy.

Italy has always had characters such as Giovanni Bernaschi. But perhaps the most odious character is Dino Ossola, the striving bourgeois who is so greedy he imperils his business, his relationship with Roberta and his daughter’s future. Italy has always been a conformist country. Now it is a conformist country and a consumerist country; a volatile combination. While “Berlusconismo” is certainly a catalyst, what other factors have come together to create this particular crisis in Italian society?

I’m interested and amused that you use the adjective “conformist” to describe a country like Italy and a people like the Italians. Another hundred words come to my mind, especially to describe the historic moment that you call “Berlusconismo”: slackers, suckers, fatalists, male chauvinists, rule-benders, with an ancestral sense of the family in the name of which crimes large and small are committed every day, and I could go on . . . but “conformist” is not wrong. Without a doubt Italy is a consumerist country, like all the countries in the capitalist world. The years of Berlusconi marked a fatal rupture with what was traditionally considered – also by the conservative bourgeoisie – a world of preeminent values: culture, the heritage of identity, history, memory. We have become a more vacuous people who – on the contrary of the commonplace according to which we are elegant people with a lust for life – dress horribly, eat badly, and don’t know how to have fun.

How do you see your film in the context of the history of Italian cinema with a social and political consciousness? Can you tell us about the influence of Gianni Amelio and Furio Scarpelli on your work?

PV: Gianni and Furio were, respectively, my directing and screenwriting teachers at the film school I attended more than thirty years ago, the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, in Cinecittà, Rome. Furio Scarpelli, who was one of Italian cinema’s greatest writers, was kind enough to hire me to work for him when I was only twenty one. For the first few years of cutting my teeth, I was his assistant, and from him I think I learned almost everything, in particular a passion for mixing tragedy and irony, in a highly-satirical but also very humanistic cinema, with a marked sympathy for the lower classes. From Gianni I think I tried to steal a kind of visceral manner of conceiving cinema, of becoming passionate about the magic in the moment of shooting, as well as a passion for the world and for people and at the same time for cinema as a possible medicine that makes life livable.

What is the relationship between commedia all’italiana and political films?

Too many different things are grouped together under the expression “commedia all’italiana.” But there are at least a dozen Italian films, with performances by popular Italian actors like Sordi, Gassman, Manfredi, and Tognazzi, that are the true political novels of our country: We all loved each other so much, The Great War, The Terrace, The Family, Il Sorpasso, The Birds, the Bees, and the Italians, Divorce Italian-Style, The Organizer. I have given you eight titles, but I could easily name another dozen. And it’s no accident that five or six of these were written by Furio.

You have often been influenced by literature (Italian and American) in your work. Can you explain the particular benefits and problems of working with a literary text?

I think I’ve always had a licentious and never reverential relationship with the novels that I’ve used as the basis for conceiving a film. And every time I think I’ve adapted them with great respect, but above all as a vehicle for going somewhere else.

Can you tell us something about the musical score by Carlo Virzì?

We were trying to create a mysterious, sardonic atmosphere that would not evoke the Italian musical tradition. We were looking for the echo from another place. Carlo used musical instruments from Vietnam, Japan, India, and Australia. They inspired him to imagine Brianza as a jungle where nature, especially in winter, becomes threatening and, if you look at it in a certain way, seems about to swallow up the mansions of the rich, the little houses of the social-climbing lower middle class, the malls, the decayed working class districts, everything. The contemporary idea of affluence – which already seems obsolete – can no longer guarantee certainty or hope; this idea seems to have collapsed in order to be absorbed by the barbarous nature of these places.

This is your second film to represent Italian cinema at the Academy Awards (“La prima cosa bella” was the first). And for the second year in a row, Italy has had two great films at the Oscars. Is this a sign of a rebirth of Italian cinema or simply greater recognition in America?

With all my personal respect and even veneration for American cinema and for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, for the great films shot in the United States, I’m not sure we should measure the reputation, credibility, and health of our cinema solely through the recognition of the Hollywood community. If you want to know my opinion of contemporary Italian cinema I sincerely believe that it is one of the most lively and interesting in the world, but do bear in my mind that I might have a certain bias.

What are you working on now and what future projects do you wish to complete?

I’m working on a new film that I will shoot between spring and summer, which will be ready probably for 2016. It’s an Italian film that will be shot primarily in Tuscany.

* Dr. Stanislao Pugliese, Distinguished Professor of Italian and Italian American Studies at Hofstra University

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.