Alberto Giacometti: The Core of Life

Not in this lifetime will you find a better setting for the 200+ works of Alberto Giacometti than those on display today.

That’s the first impression you get upon entering the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which Frank Lloyd Wright designed, despite his commission, with a view to building “the best possible atmosphere in which to show fine paintings or listen to music.”

That was the gist of all the comments made at both the dinner and opening press event by the museum’s director Richard Armstrong; Francesca Lavazza, a trustee and sponsor of the show; Catherine Grenier, director of the Giacometti Foundation in Paris; and Megan Fontanella, co-curator of the show.

Stanley Tucci (actor and director of the 2017 Giacometti picture Final Portrait) captured the impact well when he spoke about the negative and positive space that the artist’s sculptures manage to delineate, evoke, communicate. (By the way, it was a weird coincidence and a weird meeting, since Stanley and I narrated the upcoming documentary about Tintoretto produced by the National Gallery in Washington.)

But why are we speaking in English about a Swiss artist for an Italian magazine? Should we think of Alberto Giacometti as Italian?

Well, in one sense, yes. In part because Giacometti himself frequently said that he felt more Lombardian than Swiss, seeing as he was born in that Italian canton. Giacometti was actually born in Borgonovo di Stampa, in Canton of Grisons (Switzerland) on October 10, 1901, to the post-Impressionist Swiss painter Giovanni Giacometti and Annetta Stampa, a descendant of Protest Italian refugees from Switzerland.

He was also intensely attached to his native land and almost violently devoted to his family, as his sculptor and friend Mario Negri pointed out in his documentary for Swiss television in 1986.

Giacometti began drawing, painting and sculpting at a very young age. Impressed by his talent, his parents sought to encourage him. There is a famous clay portrait of his mother from his high school years at the Giacometti Foundation in Stampa, in the Val Bregaglia, Grisons, Switzerland. Founded in 2013 and distinct from the Giacometti Foundation in Paris, who is the co-sponsor of the current show.

In 1921, the then twenty-year-old moved to Rome to study, among other things, the great artists of the past.

During his studies, he took a particular shine to the work of Tintoretto and Giotto, who inspired him to create art that eschewed intellectualism and drew from primitive origins.

At the same time, he also took an interest in anthropology and African art, an interest that resurfaced in many of his creative stages.

Archaeology was another subject of interest, in particular Etruscan art, which he first came across at the Museum of Archaeology in Florence. It would influence many works, such as “The Chariot” of 1950. The same was true of Egyptian sculpture, which can be seen in many statues and busts from 1940 on.

Upon returning to France, he came under the spell of Cubism. His work from this period makes constant reference to Brancusi and Archipenko. Look carefully at the first part of the show and you’ll discover where he converges with and diverges from the two artists.

It’s really an open (art history) book.

In 1927, Giacometti became part of the Surrealist group (despite participating in shows with them till 1938, by 1935 he’d already broken from the group). His first surrealist sculptures were displayed at the Salon des Tuileries

During these years, he formed an important bond with the movement’s founder, Andre Breton, and contributed to his magazine, Surrealism in the Service of Revolution. But the revolution proved very intimate, painful, freeing:

“Yes, I make pictures and sculptures, and I have always done so, from the time I first started drawing or painting, in order to denounce reality, in order to defend myself, in order to become stronger in those things with which I can the better defend myself and launch my attacks; in order to stave off hunger, cold and death; in order to be as free as possible, free to strive, with the means that today appear to me as the most suited to this task, to see and to understand my environment better, to understand it better so that I have the greatest measure of freedom; in order to squander my powers, expend all my energy as far as a I can into that which I create, to have adventures, to discover new worlds, to wage my battle—for pleasure? out of joy?— a battle for the sake of the pleasure of winning and losing.”

His is a career of constant extremes, I’m moved to say, constantly torn between competing forces, as we can see throughout his career as both a painter (the current show has a wealth of drawings and canvases) and sculptor.

During his surrealist period, the imagination and (oftentimes) the unconscious are the guiding principles that form the base of Giacometti’s sculptures, which are very important to the surrealist idea of “objects with a symbolic function.”

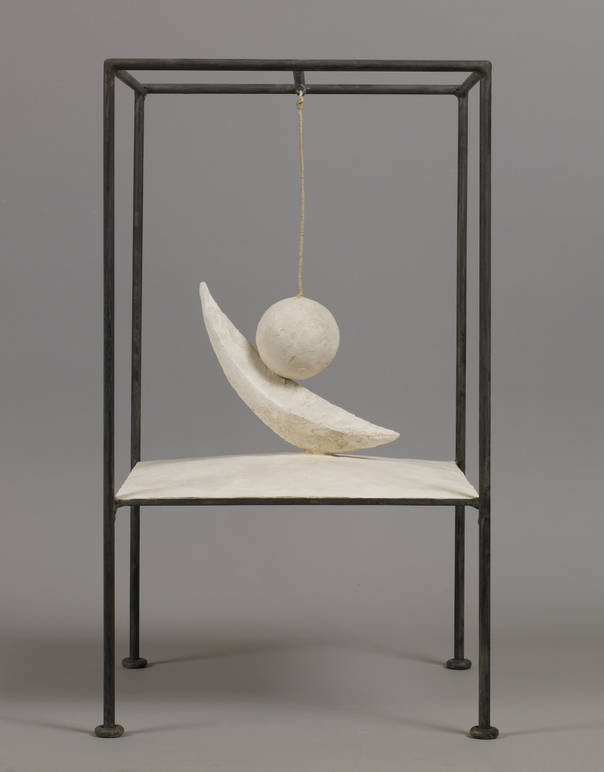

That gave rise to “Boule pendu” (Suspended ball, 1930). A ball hanging on a thread rests on top of a halfmoon inside an iron cage. The sculpture, a standout as you wind your way through the spiral museum, introduces the problem of spatial limitations, which would become a constant in Giacometti’s esthetics.

In the sculptures from the early 1930s, a period well represented in the show, there are a few recurring elements fundamental to interpreting the work: allusions to body parts and sex organs that form a dialectical relationship with linear and geometrical shapes by being placed inside of them (“Cage,” 1931). His use of cages highlights the idea that sculpture is a transparent, visible and plastic construction of “illusory” space in painting. His friendship with Pablo Picasso during these years was fundamental.

When they first met, in Surrealist circles, the two artists already knew and admired each other’s work. Alberto Giacometti had seen the paintings of Picasso, just as the latter had Giacometti’s sculptures. In fact, the Spanish artist had attended the sculptor’s first Parisian show.

It was a point of pride for Giacometti that he attracted Picasso’s attention. He was twenty years his junior and Picasso was already considered the great modern artist of the era.

Reading Giacometti’s letters to his family, you realize the depth of his friendship with Picasso, whose hound would become the model for the sculpture that closes the show at the Guggenheim.

But the Surrealist period and his work in that vein would soon fizzle out, and Giacometti returned to figurative studies, to the “Fleeting resemblance,” as the title of Jean Soldini’s 1998 book has it. Chronologically speaking, this shift in thought is occasioned by the death of his father in 1933.

From 1935 to 1940 he concentrated almost obsessively on studying heads, beginning with the gaze, the seat of our thought. He began to draw entire figures in an attempt to capture the identity of single human being with just a glance.

His preferred subjects, few and constantly revisited, were familiar: his mother, his brother Diego, his cousin Silvio, the objects he surrounded himself with, the landscapes he’d seen and lived in.

It is here that I find extraordinary parallels to Giorgio Morandi. Both artists explore their intimate relationship with objects (or, in this case, people). It is the space between them, the way they emerge and contrast that “creates art,” whether it be two or three dimensional. The figures are fixed, immobile, strictly forward facing, isolated in space. Almost as if their presence created both an emptiness and fullness, so that what emerges is a “metaphysical space.” The figures are made of “lines of force” covered with amorphous materials that carve out the surroundings. This pursuit became a real obsession.

“From 1935 on, I never did anything the way I wanted. What emerged was always something different from what I wanted. Always.”

Almost never, with the exception of the eyes (“Mains tenant la Vide” or Holding the Void, “Objet invisible” or Invisible Object). Their outline is drawn, but the viewer is left to imagine the pupil. Everything is placed in an inaccessible dimension in which the circumscribed space is the essential component. It’s the artistic transposition of Sartre’s existential theories; no coincidence that he wrote an essay for one of Giacometti’s shows and became a partner in crime.

The artist/sculptor spent World War II in Geneva, for he couldn’t return to Paris, and that is where he met Annette Arm, his future wife.

In 1946, after the war, he returned to Paris and was reunited with his brother Diego. He immediately launched into a frenetic phase of activity, during which his sculptures became elongated, their limbs extending into a space that contains and completes them.

From 1950 on the figures were more often alone, though groups of figures inhabit the same space. It’s the space between them that establishes their relationship. Not the gaze but the approach to “similitude” that is the key to read and interpret their relationship.

In Giacometti’s elongated figures, we recognize the figures described by Proust at the end of In Search of Lost Time: «comme si les hommes étaient juchés comme sur de vivantes échasses qui grandissant sans cesse finissaient par leur rendre la marche difficile et périlleuse, et d’où tout d’un coup ils tombaient».

We are all hovering on the edge of lost time.

We’ve mentioned Breton, Picasso, the Surrealists, Sartre. But another figure—apparently far removed from that world—remained dear to Giacometti’s understanding of existential theory: Jean Genet, who wrote a beautiful essay about his friend.

Picasso thought it was the most beautiful essay on art that he’d ever read. It’s easy to understand why he was so enthusiastic; L’atelier di Alberto Giacometti, which came out in the magazine Derriere le miroir for the first time in June 1957, is an incisive, intense and illuminating piece.

“As I see it,” writes Genet, “Giacometti’s work makes our universe even more unbearable. It seems, in fact, as though the artist knew how to lift the veil from our eyes to reveal what remains of man when all misleading appearances have fallen away.”

Genet felt Giacometti’s sculptures were the key to beginning the process of recognition and stripping away, a process every creature must complete: you need to shrug off the visible world and venture beyond what can be measured, beyond the appearance of reality.

It was a “testament” for both beings, an essential, unusual yet real bond between the arts that the two men represent.

It turns out this process is interminable for the artist who stubbornly pursues a goal that, mysteriously, eludes him. ”I have the feeling,” he says, “or the hope, that I am making progress each day. That is what makes me work, compelled to understand the core of life.”

Then came the glory years. In 1955, the Arts Council Gallery in London and the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York put on major retrospectives of his work.

In 1961 he received the Carnegie Prize and the year after the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale, where a space was reserved for his work alone.

There were other important shows at the Tate Gallery in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Louisiana Museum in Humlebaek, Denmark, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. That same year the French government awarded him with the Grand Prix National des Arts. But perhaps the greatest honor was when the artist and some of his works were printed on the Swiss 100-franc note (!!).

He died of heart disease in Chur, Switzerland on January 11, 1966.

You could talk for hours about Giacometti and unravel his intense and contentious relationship with America and various institutions, or talk about the acquisitions that, slowly, made him one of the most sought-after artists of the 1900s. But more importantly I encourage you to go see this show. Then maybe we can reconvene to talk about him. Sound good?

While you’re at it, check out the three bronzes on sale in the Galleria Venus on 980 Madison Avenue. You won’t regret it!

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.