Food, Fashion and Film Explored at the Calandra Institute

Thursday, April 28. The Calandra Institute held the opening reception for conference with opening remarks by Katherine Cobb, VP for Finance and Administration of Queens College, CUNY; Matthew Goldstein, CUNY Chancellor; and food and travel correspondent for Esquire magazine John Mariani, who presented on “How Italian Food conquered the World”, followed by food and refreshments, of course.

On Friday Anthony J. Tamburri, Dean of the Calandra Institute, presented his work within the panel called “Fashioning Style in Reel/Real Life”, chaired by Dennis Barone of St. Joseph College. The title of this panel indicates the themes of Italian fashion as underlying cultural signifiers in film and beyond the reel. Dean Tamburri’s presentation, “Micheal Corleone’s Tie: Signifying Ambiguities in Coppola’s The Godfather”, explored how a seemingly simple stylistic choice, like a film character’s tie, can render meaning in the context of the film and for Italian American culture portrayed on the big screen. He pointed out that in one scene of the film in which Don Corleone meet’s with businessmen who are professionally dressed, the Don is sporting a green tie with a red shirt. This tie-and-shirt combo symbolizes his role as the Italian American grandfather, and is juxtaposed with the standard American business attire of white shirts, black ties and jackets. Hence the choices directors make about the fashion in their films are purposeful are open to critical interpretation.

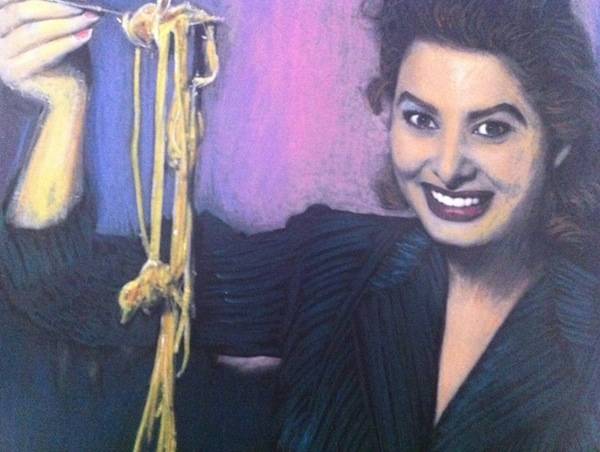

Another fascinating panel on Friday entitled “Food and Its Discontent” was chaired by author George De Stefano, who gave a provocative talk about the cinema of Ferzan Ozpetek the following day. The three extraordinary panelists discussed how food played pivotal roles in their lives as Italian American young women.

Lulu Lolo, a performance artist, vividly recounted in “Growing up Italian American in a ‘Wonder Bread’ World” how food served as a connection to her heritage, especially to her grandmother. Lolo verbally re-enacted her early life in East Harlem’s little Italy, and how she forged a bond with her grandmother who knew little English, while Lolo herself knew no Italian. The inability to communicate with her nonna from Potenza was assuaged by the act of eating; they had lunches together in which Lolo was introduced to ‘exotic’ foods like persimmons, taralli, and fresh pasta. These foods contrasted with the bland American peanut butter and jelly sandwiches she encountered outside her family eating experience. Lolo also explained that she learned to become an artist by watching the ‘sculptures’ of fresh pasta made by her grandmother.

In Maria Terrone’s presentation, “Food for Survival: A Memoir”, we learned how the exploration of new foods and cooking helped her steer away from the anxiety and despair that she was confronted with when she was young and unemployed, living in New York in a time, like today, when finding work was a daunting task. The daughter of Italian immigrants from Sicily who shunned away from strong ties to the old country through rebelling against food traditions, Terrone re-established her heritage as Italian American by exploring and mastering new recipes. As 23, unemployed and living in the Bronx (because of the cheap rent) with her husband, Terrone attained self-affirmation by ‘roaming the culinary maps’ that charted her back to a centered self with a purpose. Not only did cooking bring her joy, it helped her survive a difficult time and reclaim her identity.

Rosangela Briscese’s memoir, “Sliced Thin: Anorexia in an Italian-American Adolescence,” recounted her struggle with food as a young woman. Beginning her presentation with a quote said during her teenage years in which a classmate says, “it must be impossible for Italians to be anorexic”, Briscese took the audience to a time when she was more than a little obsessed with food, caloric intake, and the ingredients in her mother’s cooking. She explained the ‘cycle of control and results’ that she went through as an adolescent who struggled to be in control of something. Food was something that she tried to control in her life, and with Italian parents who ate wholesome food and found it very difficult to understand why their daughter wanted low-fat mozzarella, she found herself taking her obsession with food to higher levels until it became dangerous. A battle over controlling her own diet escalated into a disease which led her to being hospitalized, although over time, she took control of the disorder. She reacquainted herself with being able to eat again the Italian food that she always loved, as well as include new and exotic ones into her diet.

Dozens other presentations from the conference can be found here.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.