Diario Proibito: The Forbidden Diary of Mario Fratti

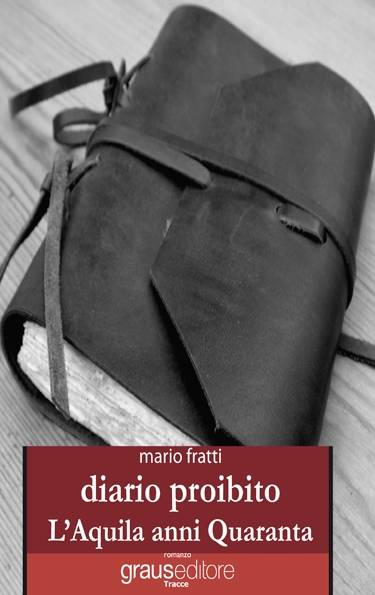

The word “forbidden” immediately implies something dangerous, prohibited, against the rules... and indeed Mario Fratti's recently published book Diario Proibito (Forbidden Diary), Graus Editore, encapsulates all these definitions. Written in 1958, while Fratti was a student at Ca' Foscari University in Venice, Diario Proibito is a homage to political commitment, and a first-hand memoir of World War II. The book will be presented by the author on March 4th at 6 pm at the Italian Cultural Institute of New York, in a panel featuring former Director of ICI, journalist and writer Claudio Angelini and Francesco Bonavita, Professor at Kean University.

Playwright, actor, and drama critic Mario Fratti is a well known figure on the literary and theatrical scene in the US. He was born in L'Aquila 1927. and his his theatrical career began in 1957. He moved to New York City in 1963. Several of his (91) plays have been translated and performed in 19 languages (e.g. Cage, Victim, Refrigerators, Academy, Bridge, Passionate Women, Trio, Quartet, Che Guevara etc. ) and have granted him many Awards. Among them, seven Tony Awards for the smash hit Broadway musical Nine.

We had a chance to speak with him a few days before the presentation and here are some fragments of our conversation, pieces of a large puzzle that will be completed on the 4th at the Institute.

“I was 16 and I was friends with Giorgio Scimmia, who is one of the 9 Martyrs of L'Aquila (a group of 9 young partisans who were fighting for freedom and were killed by the fascists). It was an interesting friendship, Giorgio used to speak to me about anti-fascism, the partisan movement and of retreating to the mountains to plan actions... but I was a coward and I did not go, I did not join his group. He was just a year older than me. He told me I was smart and I could teach the partisans a lot... but I was a coward and I did not go. Then for about two years I was jealous of them: I was thinking of them fighting, there in the mountains believing in their cause, while I was at home, reading, not taking any action. Then on Liberation Day, I found out they all had been killed at the gates of the city. It was a great shock for me. So I thought it was my duty to write something anti-fascism and I wrote Il Nastro, a radio-drama and I submitted it to a competition. In it the partisans are tortured savagely but they never surrender. I won first prize, they sent me the money but the play was never aired. It was too much. So I started collecting newspaper clips of all the crimes committed by the Banda Cocci, a group acting mostly in Bologna and Milan... terrible acts of violence and torture. While I was in Venice, I was 20 then, I was sick for a few days and I wrote a book set in L'Aquila where all these crimes were happening. How did I get the idea? My imagination always runs wild, and any little thing inspires me. I saw a really handsome man one day, he was a fascist wearing his uniform, complete with a knife and a gun. He was proudly walking the streets of the city... I followed him with my gaze and I asked myself “what would he do if he were to capture some partisans? Would he act human or not? So I created a character, whom I named Mario, I still wonder if that was a mistake, who is a young lieutenant at the service of a cruel major and is an observer of a bunch of tortures. He even takes part, unwillingly, but he never refuses to act. Then there is a shocking surprise at the end, which is a characteristic of my writing, as all my pieces have a surprising ending.”

Diario Proibito is a fierce book, meaning that there are episodes that will scare you especially those focused on women and how they were treated. People will say “Was Mario Fratti really like this when he was 20 years old? I am just describing how things were. It is easy to misunderstand what I wrote... many got the impression that I am the torturer but I am Mario, the observer. I am on the partisan side but I don't want to help them. I do what the major tells me. Why? Because it's my duty. Mario is reluctant, he tries to help somehow, but it's not always so obvious. This is explained in the two introductions of the book. Read them carefully, as they explain what I am saying right now.”

“Critics say that with this book I have anticipated my theatrical world. The language is dry and direct as it is in my plays. This comment has surprised me as I had not realized that, but it's true... including my signature ending, which is a common denominator of all my works. When people interviewed me and asked when did I start writing, I always replied when I was 30, because when I was 30 I started writing for the theater. I had almost forgotten that at 20 I had written this book. Initially I tried having it published. My agent sent it to Vittorini, Mondadori, Feltrinelli, Einaudi... everybody said NO! They thought it was too much, that it would bother both the fascists and the partisans. So I gave up. I gave my brother a copy of the manuscript and asked him to publish it after my death.”

So for decades the manuscript lay forgotten in a suitcase. Then one day Claudio Angelini asked Fratti about it. “He had heard I had written a book. So I went looking for it and he took care of finding a publisher and it all happened pretty quickly.” Fratti did not edit the text, he just added at the end a one act play on the 9 Martyrs. A conversation between two of them, who wonder about Mario, the coward who could have been the 10th martyr. “I was ashamed of having survived,” Fratti confesses.

All the episode in the book are real, “Back then with no internet, I had to read all the newspapers and collect the articles. Rediscovering this novel has not inspired me to write another one. This novel's style is so old and complicated... it's almost like a James Joyce novel. I would not be able to do it again. Here in the US I have changed completely, I use a more simple language, I am very concise and precise. I don't know if Diario Proibito will be translated into English as the Italian is so complicated, I would not even attempt it.”

Meanwhile Fratti is working on a collection of poems, which he'd rather call Ritratti (Portraits), written both in Italian and in English when he was in his thirties, that will be published later in the year.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.