“When you are born, you are given an indecipherable note, in it is your entire future. The illnesses, the successes, the failures, the important encounters, everything is written on there. Even the time and date of your death.”

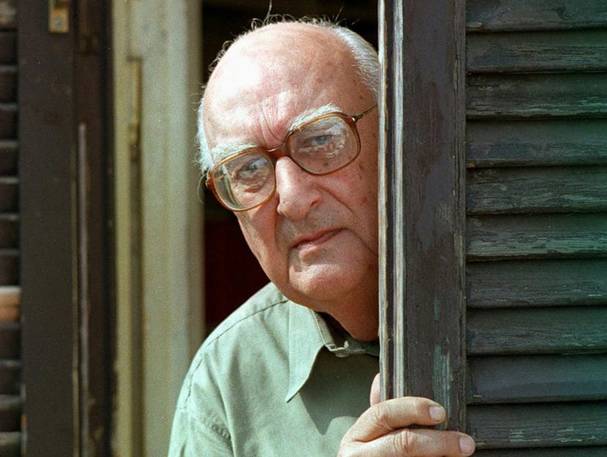

This was life according to Andrea Camilleri, who died this morning at age 93.

Known mainly as the “father” of Inspector Montalbano [2], Camilleri, born in Porto Empedocle [3] in the province of Agrigento on September 6, 1925, was a great writer, screenwriter, playrite, and director, but above all a man of the people, the creator of a language that could reach everyone. “Those who have knowledge must plant it like a seed, spend it,” he said. “Knowledge shouldn’t be for the elite, it should be for our daily use. When that will be the case, we will truly be men of this Earth.”

Not much is known of his childhood spent in Sicily, where he attended an episcopal college for four years, between 1939 and 1943, and from which he was expelled for throwing eggs at a crucifix. He resumed his studies at the Liceo Classico Empedocle in Agrigento, where he graduated without having to take any exams due to the bombardements and the arrival of the Allies in Sicily. Later, he enrolled in the Letters and Philosophy department of the University of Palermo but droped out. After the war, he joined the Communist Party and began to write and publish short stories and poems for magazines and newspapers such as L’Italia Socialista and L’Ora in Palermo and took part in literary competitions, winning some of them.

In the late 1940s, he moves to Rome, where he is accepted into the Silvio d’Amico Academy of Dramatic Arts as the only student studying to become a director that year. After concluding his studies in 1952, Camilleri takes Rai’s annual admission test, he passes but isn’t hired immediately and has to wait another three years to become a screenwriter and director at Rai. Here, he continues his career throughout the 60s working on several shows including Tenente Sheridan and Inspector Maigret. It’s only between the late 70s and early 80s that Camilleri decides to dedicate himself exclusively to writing. His breakthrough happens in 1978 with the publication of Il corso delle cose, which he had actually written ten years prior, followed two years later by Un filo di fumo. After a short break and a few unsuccessful endeavors, Camilleri returns, this time to consolidate his success.

In 1992, he publishes La stagione della caccia (Hunting Season) and in 1993, La bolla di componenda, a historical essay on the compromises between institutions and organized crime in Southern Italy. The following year, La forma dell’acqua (the shape of water) comes out, his first detective novel featuring Inspector Montalbano, succeeded by Il birraio di Preston, (The Brewer of Preston) which competes in the Premio Viareggio, helping him gain public success.

From then on, follows a continuous production of hits, which not even the onset of blindness in his later years can stop and which, despite his obstinate use of dialect, reach readers across regions and nations. He sells over 25 million copies in Italy and all over the world. His books sell on average around 60.000 copies and, thanks to the TV production of the Inspector Montalbano series, Camilleri becomes a TV phenomenon in addition to a literary one.

Despite his age and blindness, Camilleri never stopped working and doing what he was born to do: telling stories. In addition to novels, he also chose other forms of narration, performing, for example, at the Teatro Greco in Siracusa, in the role of Tiresius, the blind prophet from Thebes who shows Ulysses the way back in the Oddyssey. A character with which he shared more than blindness: the ability to better “see” and show the truth to those who, despite having eyes, cannot do so themselves. Shortly before the fatal heart attack that struck him on June 17th, he was getting ready to go on stage on June 15th, at the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, to perform his Autodifesa di Caino. Unstoppable and full of energy up until the very end, in line with what he always said: “If I could, I would like to finish my career telling stories in a square and at the end of my tale, go through the audience, hat in hand.”

However, his popularity is certainly due to Inspector Montalbano, in whose novels we’ve seen, other than his investigations, also the presence of real Italian news events such as the G8 in Genoa, immigration, corruption in the public sector, firing of factory workers, and the ability to “read” humanity in all its forms. Up until Il cuoco dell’Alcyon, which came out on May 30th and is already on top of the charts. The reflections of Salvo Montalbano, who in each novel comes face to face with a world he struggles to understand, are the same doubts of Camilleri himself, Montalbano’s alter ego. The author, especially during the last years of his life and up until his last lucid day, contemplated contemporary Italy, not shying away from expressing his opinion regarding even the most heated political debates, such as Matteo Salvini’s use of the rosary during rallies. Inevitably, his words provoked the reaction of haters, and even disappointed some of his readers who would have wanted him to remain exclusively a novelist.

The Montalbano-Camilleri pair is inseparable in the collective imaginary of his readers and, by the author’s design, it will remain so even after his death. In fact, the last chapter starring the legendary inspector will be, according to Camilleri’s wishes, published after his death and the end of Montalbano will forever coincide with the end of his author.

Every novel is set in his beloved hometown, Porto Empedocle, which becomes in his numerous writings, the imaginary and irreplaceable Vigata, an abstract place with a very real outline. A place that the Sicilian author knows very well and manages to make his readers know too. Many of them fall into the “trap” of organizing pilgrimages in search of the smells of Montalbno’s Sicily, which many won’t find because, like Vigata, it doesn’t exist geographically. What does exist is a place made up of colors and flavors, of unforgettable dishes, of dishonest people but also many good ones, who love justice and fight for it despite everything.

It’s the Sicily of Salvo Montalbano. It’s the Sicily of Andrea Camilleri.

Source URL: http://test.casaitaliananyu.org/magazine/focus/art-culture/article/andrea-camilleris-indecipherable-note

Links

[1] http://test.casaitaliananyu.org/files/andrea-camilleri-830x625jpg

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salvo_Montalbano

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Porto_Empedocle