ROME – Reading is tending to wane in Italy as elsewhere, and the number of those saying they had read at least one book in the past year dropped from 43% in 2013 to 41.4% in the year 2014, according to the national statistics-gathering agency ISTAT. But at the same time those reading at least one book a month stands at a healthy 14.3%; women and city folk read more (48% and 51% respectively).

So what do they read? A fascinating website collects contributions from train, tram and bus passengers all over Italy describing what fellow commuters are reading, with details like “stunningly beautiful, wears pony tail, carries a strap handbag, elegantly dressed, cell phone in hand.” (See

>>> [2] )

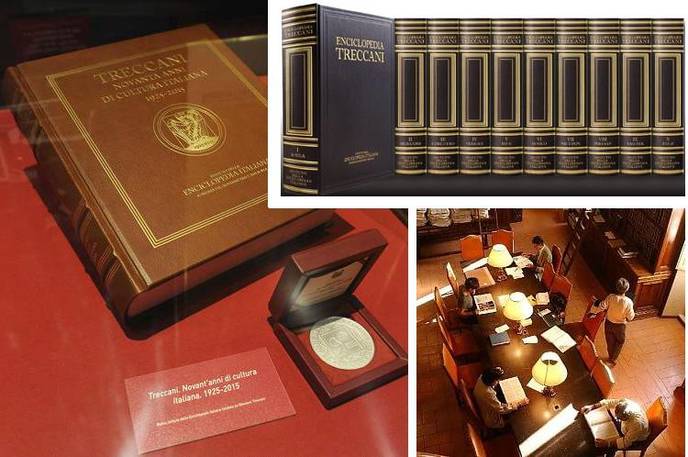

But before we pry into Italian commuters’ choices of book and look, please take a moment to honor the Golden Oldie of Italian letters, the Treccani Encyclopedia, this year celebrating its ninetieth birthday with production of a commemorative medal and an exhibition in Rome called “Treccani 1925-2015: La Cultura degli Italiani,” open through May 24 in Rome in the Vittoriano, off Piazza Venezia. The encyclopedia was founded by textile magnate and philanthropist Giovanni Treccani degli Alfieri (1777-1961) of Vicenza on Feb. 18, 1925.

Born into a farming family, at age seventeen Treccani migrated to Germany, where he learned textile production at Krefeld, the famous “city of silk and velvet” which is still the center of the German textile trade. Returning to Italy in 1898, Treccani worked his way up from technical designer for Lanificio Rossi to ownership in 1922 of a failing textile company he revived and expanded, Cotonificio Valle Ticino before returning to Lanificio Rossi as president. He was then elected to the Italian Senate where he met the famous philosopher Giovanni Gentile, and in 1915 began projecting creation of a great national encyclopedia that would cost him the gigantic sum of 54 million lire. Under the direction of Gentile, the first volume appeared in 1929.

By 1937 thirty-five volumes had been issued, for a total of 35,000 pages with 800 color illustrations and 60,000 in black and white. These were the years of Fascism, and Mussolini used the Treccani to promote Italian culture, but among the 3,200 Italian and foreign scholars who contributed the texts were many anti-Fascists, according to journalist and author Luca Valente, writing in the “Giornale di Vicenza,” June 23, 2007. (See:

>>> [3])

In the encyclopedia was an entry – the first in Europe – dedicated to “Cinematografia” (cinematography). Seventy years later Treccani issued an entire volume on the topic, “Enciclopedia del cinema” (2003), with entries by famous writers and director like Enzo Siciliano, Luigi Squarzina, Luca Ronconi and Morando Morandini. Another prestigious volume was the “Enciclopedia del Novecento,” a panorama of the 20th century published in 1975 with entries by noted intellectuals like scientist Rita Levi-Montalcini, art historian Giulio Carlo Argan, economist Paolo Sylos Labini, French theologian Jean Danielou and Israeli politician David Ben Gurion.

This morning’s subway reader at 7 am in Milan – the gorgeous girl with the pony tail – was reading “Expo 58” by Jonathan Coe. “She’s leaning against the back wall, crosses her legs and is totally engaged in reading. Tries not to lose her balance, she is serious, never raises her gaze from her book,” writes contributor Riccardo Tommasini.

In his March 30 entry on the site, the thirty-something author Paolo Di Paolo of Rome confesses that, “I have the sickness of looking at the books of people reading, in the bus, train, plane, subway, on all sorts of transportation and on benches…. What surprises me are the eccentric books that aren’t on best-seller lists, not out of snobbishness but because they make me ferociously curious.” That day’s book catching his fancy was “Aden Arabia,” by Paul Nizan with a prologue by Jean Paul Sartre. “I’d like to ask her questions. And like to question the boy on the subway in Rome reading Stefan Zweig: was it because of the movie made by Wes Anderson?” His conclusion: “This story is the voyage that changes us.”

Did it also change the Neapolitan man on the subway carrying under arm a copy of the “Decameron”? “He does not seem distracted, rather a human being who is pausing, though we can’t know from what…. If I had a simultaneous translator I’d perhaps be able to guess have of those thoughts locked between slowdown and actions.” He wears green trousers and eight little earrings, adds the anonymous author.

From a crowded train, here’s an entry signed by Christian Caldato: “He has a rolling suitcase beside him, with the outside flap left open. Where he’d put the book there’s now space waiting to take it back. He has short hair, casually unkempt but in a way that evokes order. Wears a green sweater.” He’d just begun to read Philip Roth’s “Pastorale Americana,” and “never lifts his chestnut eyes from the pages.” The book looked as if he’d bought it on sale, adds Caldato.

And now, from another subway in Rome, another translation from English, in this contribution from an unidentified commuter: “There’s this guy leaning against a post, he seems a devoted youth, judging by his tidy clothes and the little book he’s holding. First I try to see if he has a clerical collar; he does not… but he has nostalgic velvet trousers and the sort of cap old people wear.” What’s he reading? A volume of Emily Dickinson’s letters entitled “Un vulcano silenzioso, la vita” (A Very Silent Volcano - Life,” written in the mid-19th century and translated by Marco Federici Solari (Orma Editori, 2013). Fascinated, the commuter admits he’d love to speak with this person whose existence appears out of space and time, but, alas, “I have no choice save to get off the train.”