AMELIA – For the sixth year in a row experts from sixteen nations convened in this tranquil city set amid the rolling green hills of Umbria, 100 miles north of Rome, for an interdisciplinary conference on art crime, held in Amelia June 27 – 29. Among the speakers from as far away as New Zealand and New York were archeologists and art historians, police and intelligence officers, attorneys and sitting judges.

Crimes destructive to the heritage occur not only through the sale of forgeries and the looting of museums, churches and private collections, but also in wartime. On hand, therefore, revealing how he works under cover to protect the heritage in wartime, was also a real-life “Monuments Man” who had in fact been consulted by George Clooney prior to the making of the film Monuments Men. (“But let’s face it: Clooney is just too old to play me,” the real one joked.)

Art crime, needless to say, is no laughing matter. This unique convening of detectives and bookworms, Interpol officers and forensic archaeologists is organized annually by Prof. Noah Charney, president of the Association for Research into Crimes against Art and chief editor of the semi-annual “Journal of Art Crime.”

Art crime and restitutions have been a burning issue for literally centuries - to wit., the never ending quarrel between the British Museum and the directors of the New Acropolis Museum over ownership of the Elgin Marbles (or, as Greece would have it, the Parthenon Marbles), removed from the Acropolis and shipped to London before 1805 by Lord Elgin, at the time British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

The wholesale news coverage of the trial in Rome of Marion True, the then J. Paul Getty Museum curator of antiquities; of American antiquities dealer Robert Hecht; and of the convicted Italian trafficker Giacomo Medici rekindled international interest in the subject. Following that trial, which began in 2007, the Getty Museum in Malibu was obliged to make restitutions to Italy of important looted antiquities. Not only the Getty was involved: the Metropolitan Museum was forced to return to Rome an important ancient Greek vase signed by Euphronios, which was reportedly purchased for $1 million. As a result of that trial museums in Cleveland, Boston and elsewhere were similarly forced to make restitutions to Italy.

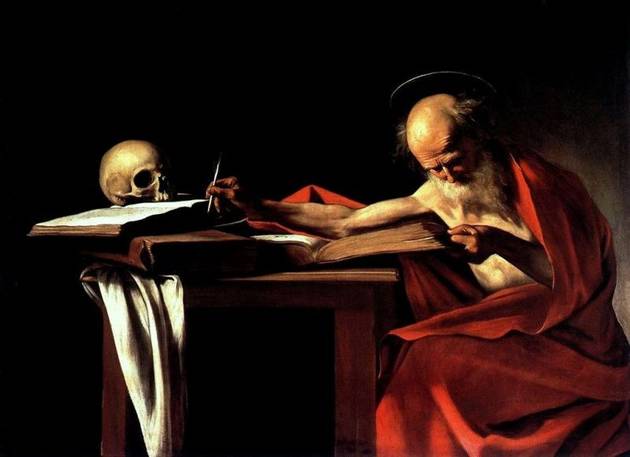

In some cases the Mafia has been involved in a major theft. The Rev. Dr. Marius Zerafa, former director of museums at Malta, spoke on the 1984 theft from the Co-Cathedral of St. John of Caravaggio’s late painting “St. Jerome Writing.” Zerafa is the Dominican priest who successfully traced and then personally handled the tense ransom negotiations with the Mafia, which resulted in the painting’s successful return.

Another newly notorious case was deeply political. In what is called “the Gurlitt affair,” German art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, acting for the German state, assembled a giant cache of art works which the Nazis had termed “degenerate.” When he died in 1956, this completely unknown collection of 1,300 paintings passed to his reclusive son Cornelius, as was learned only in late 2013, when Cornelius fell under suspicion of tax fraud. This May Cornelius agreed to turn over the works to the German government. It was a deathbed agreement: Cornelius Gurlitt died that very month. The legal in’s and out’s remain complex, for Bonn must now seek the heirs of the original owner of each work.

Rome attorney Massimo Sterpi spoke of the compendium he co-edited with Bruno Boesch for collectors on comparative international laws for thirty countries in “The Art Collecting Legal Handbook” (London: Thomson Reuters, 1013). Important art fairs are held worldwide: in Florida, Basel, Istanbul, Toronto, Hong Kong, and other even more far-flung venues. For today’s collectors, knowing the variations in the rules that apply in different countries (taxation, laws on exports and imports, donations and so on) is ever more important because of the globalization of the art market.

Dr. Roberta Mazza, an Italian scholar at the University of Manchester and an expert on ancient papyri, described how casual collectors have used bars of ordinary soap so as to dismount mummy masks and hence destroy the papyri while so doing. After being wrapped in linen bandages, mummies were encased in recycled papyri, or what has been called “papyrus-mache’” coverings (cartonnage).

In Italy today, museums are better protected than in the past, and the Internet permits a closer look at what goes on the market, including stolen objects. As a result, all heritage thefts dropped by almost one-third in a single year, 2013 over 2012. A crucial reason is the Carabinieri art squad. Their databank, now ten years old, shows five million stolen objects - some missing for decades - and almost half a million images, readily compared with items offered for sale. In addition, an app for smart phones named iTPC will soon be connected to this databank. Potential buyers, from individuals to auction houses, have little reason not to beware of acquiring looted Italian works of art.

However, like the still unknown Etruscan tombs whose loot continues to supply the illicit antiquities market, some Italian churches are less well guarded and their collections less carefully inventoried than museums. As a result, although thefts in churches have declined numerically, they have increased as a proportion of the whole. Over 700 objects were stolen from churches in the past two years - that is, 44% or almost half of all art thefts in Italy.

Source URL: http://test.casaitaliananyu.org/magazine/focus/op-eds/article/in-umbria-arca-puts-art-crime-summer-agenda

Links

[1] http://test.casaitaliananyu.org/files/sangerolamo1404670328jpg