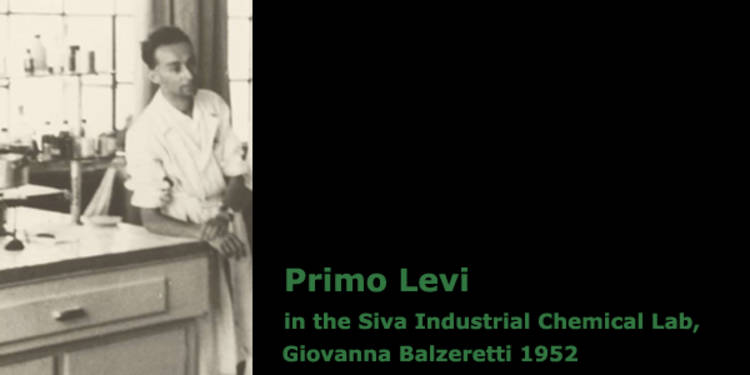

The simple mention of the name Primo Levi immediately evokes an array of images and ideas: the concentration camps, the role of a survivor, Italian Jews, a tragic death and a never-ending legacy, founded on the principles of Memory, Remembrance and truthful re-telling of a story, the passion for scientific facts.

In fact he was an Internationally known writer (If This is a Man), an essayist, an avid reader and a scientist…

[2]

Centro Primo Levi [3], the most important institution dedicated to Levi’s legacy and the study of Italian Judaism in New York, has organized the 5th annual Primo Levi Forum, November 7th, 8tth and 13th, focused on Levi’s scientific writings.

It will feature important scholars and even a staged reading with John Turturro and Joan Acocella.

Natalia Indrimi, the Director of Centro Primo Levi, has given us an enlightening and in depth personal interview, contextualizing the forum and shedding light on Levi’s passion for Science.

What are the aims and scope of the Primo Levi Forum and what is your assessment of its achievement at its 5th edition?

NI: The Primo Levi Forum convenes annually in New York City scholars, scientists, writers and artists to initiate new dialogues on different aspects of Levi’s work and further his quest on issues of justice, ethics, memory and coexistence. The idea is to explore and present these issues from different perspectives and disciplines.

We have launched the first debates seeking to desegregate Levi from the important but narrow frame of “Holocaust writer” to which he is often relegated in the US. The ideas that have emerged from the Forum and the span of disciplines and languages that have been part of the programs since 2006, show the relevance of Primo Levi in the contemporary world.

Since 2009, the Forum also includes artists whose work is inspired by or dovetails with Levi's writings. With the support and collaboration of Dr. Claude Ghez, a neurologist at

Columbia University [4] whose grandfather, Giuseppe Treves played the English horn in the orchestra of the

Teatro Regio [5] in Turin, we established an inaugural concert, performance or multimedia. This year we present the English reading "The Mark of the Chemist" which will have a full production at the

Teatro Stabile [6] of Torino. John Turturro, Joan Acocella and the composer Marco Cappelli will bring to the stage an fictional conversation based on Levi's lesser known writings which was curated by the literary critic Domenico Scarpa.

Science has a particular relevance for Levi. How does this program address it?

NI: There is little doubt that science and its conundrums shaped Levi’s perspective on society and humankind as well as his writing. While any discussion on Levi cannot ignore science, this is the first time we have chosen to focus specifically on this aspect trying to follow Levi’s “method” in investigating humanity. We are stressing Levi's specific place as a mediator between the worlds of science and the humanities, where on one hand, he describes the organizing beauty of science as a way to comprehend the world. On the other hand, he identifies a challenge, or what he sees as a fundamental error or mishap in the profound structure of the human being. What he ironically calls a “vizio di forma.” Interestingly enough, the program was shaped jointly by a group of psychoanalysts and neurologists, mainly Lice Ghilardi of

CUNY [7] and Paola Mieli of Après-Coup, who were able to bracket aspects of Levi’s “science fiction” tales that literary critics have seldom discussed in depth.

This year science is emerging as a theme for many other cultural initiatives beyond the Forum…

Yes, the

Centro Primo Levi [8] in Turin and

Einaudi [9] have just published the second Primo Levi Lecture by Massimo Bucciantini (

University of Siena [10]) which explores exactly this topic and is entitled “The Auschwitz Experiment.”

Right after the Forum the

Italian Cultural Institute [11] in NY will inaugurate an exhibition dedicated to 150 years of the “Italian Genius.” These different programs shed light on a historical dilemma that Levi articulated clearly. If on one side Levi regards chemistry as the metaphor of a non-totalitarian thinking, on the other hand he is very aware of the fact that the scientific establishment, including the Italian, fully participated in the definition of biological racism as well as in the conception of the technocratic structure of Auschwitz.

Not everyone knows the dark and yet crucial personal story of the connection between Primo Levi’s survival in the concentration camps and his knowledge of science and chemistry. Can you speak about it?

NI: In Auschwitz, Levi worked during the day in a chemistry lab run by the Nazis. This spared him for some hours of the day the brunt of the camp's routine. Just as importantly, Levi's scientific background gave him additional tools to record and interpret the horrors of the camp which he viewed as a deranged, large scale, social experiment. As he writes, life in the camp cannot be described. However, by using intellectual strategies borrowed from science, he is able to both “report” and, within limits, he clearly defines, “bear witness.” Most significantly, Levi asks the universal question on the extermination machine – “how could a civil society produce Auschwitz?” In two directions and continues to look for what Auschwitz left in our “civil” society.

Judaism, especially in American pop culture, has always been connected with psychoanalysis and the drive to research, to question, to compare and contrast (as done in Talmudic studies) in an almost scientific way. Can you describe the ways in which science, Judaism and the relentless wish to remember, shaped Levi's identity?

NI: Levi often repeated that as a young man, being Jewish coexisted with other aspects of his identity. Auschwitz inexorably forced him to confront and identify as a Jew in the most dramatic way. He expressed with the metaphor of the Centaur, the complexity of his identity, as a chemist and writer, and most fundamentally as a man. The Centaur represents the coexistence of opposites, the union of man and beast, of impulse and ratiocination. The tale of the Centaur explores a particular meaning of freedom that we also find in Levi’s version of the legend of the Golem. If it makes any sense at all to try to attribute a cultural origin to an idea, in conceiving the Centaur, I suspect that Levi follows a very important line of Jewish thought. In the Centaur, he is able to embrace and perhaps even put to work that “vizio di forma” he found in humanity.

*****

Monday, November 7th at 7:00 pm at the

Museum of Jewish Heritage [12], Edmond J. Safra Hall, Battery Park: The Mark of the Chemist: A Dialogue with Primo Levi. A staged reading from Primo Levi’s writings on science featuring John Turturro and Joan Acocella, with a soundscape by Marco Cappelli.

Admission is $20 and $15 for members of CPL and MJH.

Tuesday, November 8that 5 pm at NYU

Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimó [13], 24 West 12th Street: Science and Dystopia: Primo Levi on Science Fiction. Free admission.

Sunday, November 13th, at 9:30 am, Rabbi Philip Graubart (Congregation Beth El, La Jolla) and Natalia Indrimi (Centro Primo Levi, New York) will discuss Primo Levi’s science fiction stories and Levi’s place among 20th century Italian Jewish writers. The event will take place at the San Diego Jewish Book Fair.

[2]

[2]