How might the U.S. presidential race present a moment to consider the role of race in Italy and the U.S.? Having read Ottorino Cappelli’s [2] and Maria Laurino’s [3] recent posts on the topic, I thought I’d take things into a new direction of sorts.

The subject of Italian Americans, race, and politics brings together two topics of particular interest to me: the role of memory in the creation of an Italian American white ethnic identity and the terms used to talk about different generations of post-immigrant “ethnic” individuals. And in this sense, I agree with Laurino’s and Cappelli’s respective views that the current election brings to the surface important issues about race and identity in the U.S. and Italy.

One intriguing issue related to the question of Italian American whiteness is the way in which popular memory contributes to the creation of identity. Whatever we call it (popular memory, public memory, collective memory, cultural memory, historical memory), shared recollections in part construct “a group, giving it a sense of its past, and defining its aspirations for the future” (

as James Fentress and Chris Wickham put it [4]).

The display of that memory—in what we read, what we watch, how we dress, how/if we worship, how we vote—becomes in part how ethnic identities become codified within larger social and cultural structures. Anthropologist Micaela di Leonardo in looking at Italian American communities considers how these memories more often than not become sentimentalized, especially around issues of gender, race, and class, creating a

“rhetoric of nostalgia” [5] about a past that never existed.

This kind of selective popular memory leads to,

as I’ve argued elsewhere [6], the reliance on stereotypical images of Italian American men and women in cinema, among other places. This nostalgia, what Jennifer Guglielmo refers to as a loss (“Italians were not always white, and the loss of this memory is one of the tragedies of racism in America,” in

Are Italians White? How Race Is Made in America [7]), might very well be connected to how individual Italian Americans think of themselves and, in turn, the choices they make in the voting booth.

Italian American identities, as the I-Italy site makes very clear, are vast and complex. And yet when we exercise our right to vote we align ourselves with likeminded voters, and in so doing cement our own identities as belonging to some greater community (surely not only an Italian American one!).

This discussion of the construction of identity is in great part an academic one alone. (In other words, individuals’ everyday lived experiences are caught in very real and very messy combinations of how power plays out with race, class, gender, and sexuality.) And so we might consider the role language plays, but not though with regard to identifying terms and slurs used for different groups (think of that great clip from Do the Right Thing that Cappelli uses in his post).

Instead, I’d like to bring up the failings of both English and Italian to have given us specific words to help us remember the past, especially in relation to Italian migration. I’m thinking of words like those that exist in Japanese, words that describe the variety of Japanese transnational migration.

Here are a few of the terms, now part of American English:

~ Issei

The generation who emigrated from Japan, generally referring to pre-WW II emigration (not eligible for U.S. citizenship until 1952).

~ Nisei

The first generation born abroad, generally of an issei couple.

~ Sansei

The child of a nisei couple, or the second generation to be born abroad.

~ Yonsei

The child of a sansei couple, or the third generation to be born abroad.

~ Kibei

An individual of Japanese descent born in the U.S. but mainly educated in Japan.

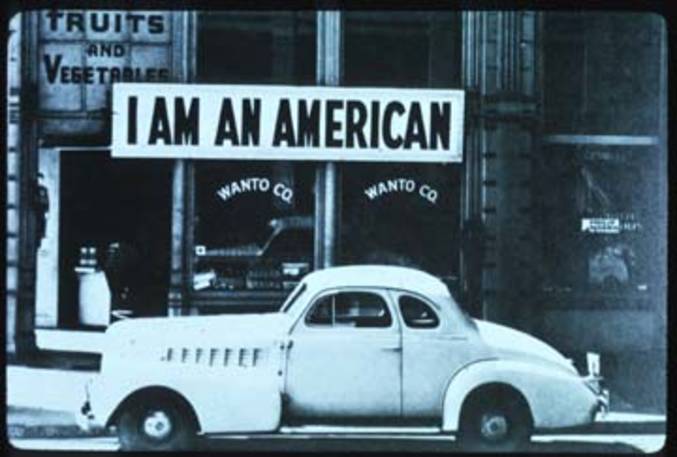

If adopted uncritically such terms no doubt may actually obscure rather than clarify. On the other hand, these terms have come to underscore legal issues related to race and citizenship rights in U.S. history (click image below to view this recent satirical take on that history care of The Onion).

("U.S. Finally Gets Around to Closing Last WW II Internment Camp")

I wonder at times what the upshot might be if we had such words to talk about Italians. Terms in any language that would begin to clarify some of the nuances of the history of the Italian diaspora could perhaps be one way to keep nostalgia at bay (and if the world turns my way, keep progressive politics at the forefront).

The result (perhaps a tad oversimplified) might be Italians who, faced with new immigrants in Italy, remember their brothers’ and sisters’ own history of migration, and Italian Americans who, faced with new choices for president, remember not to look at the past through rose-colored glasses.

------------------------------------------------------------

Select Bibliography

di Leonardo, Micaela. The Varieties of Ethnic Experience: Kinship, Class, and Gender Among California Italian-Americans. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U P, 1984.

Fentress, James and Chris Wickham. Social Memory. London: Blackwell Press, 1992.

Guglielmo, Jennifer and Salvatore Salerno, Eds. Are Italians White? How Race is Made in America. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Hayashi, Brian Masaru. Democratizing The Enemy: The Japanese American Internment. Princeton: Princeton U P, 2004.