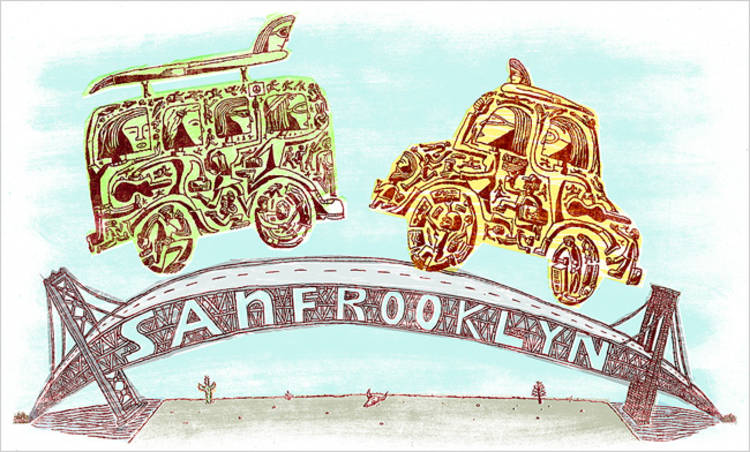

Last month I visited New York City and environs. I returned to California the day the New York Times ran a piece [2] describing the similarity between parts of San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley and Brooklyn.

Indeed, just a week earlier, as I was enjoying a beautiful day in Red Hook, Dumbo, and Fort Greene, carting my children from one public park to the next, I casually commented to my Brooklyn friends how I was pretty confident that if everyone around us had been gathered up in a tornado that day and dropped in Oakland, we would have all, sooner or later, ended up at Oakland’s Frog Park or the Temescal Farmer’s Market. Such were the similarities among us.

Although the NYT’s piece oddly conflated neighborhoods in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley, I do see a striking Brooklyn-Bay Area overlap in North Oakland’s Temescal District, which just happens to be the old Italian American neighborhood. In fact, that neighborhood’s trendy Sunday morning Farmers Market (what you New Yorkers call “green markets,” I believe), is housed in the parking lot of the local Department of Motor Vehicles, right across the street from one of only a few remaining Bay Area Italian American social clubs that actually has its own building, the Colombo Club.

The Colombo Club has something like 1000 members and a waiting list to join (a Brooklyn-transplant Italian American friend waited five years to get the call). That said, the club, for me, has a complicated relationship to Italian American identity, culture, and history.

The club—with its focus on monthly birthday dinners and large banquets—has on occasion financially or otherwise supported the study and dissemination of Italian American culture and history. At the same time they refused (along with the other main East Bay Italian American social club with a building, the Fratellanza Club) to rent out some of their space to a fledgling Italian children’s language program—co-founded by the above-mentioned Brooklyn transplant and yours truly—some four years ago. So instead, the classes, with mainly third- and fourth-generation Italian American kids enrolled, operate out of the Finnish Brotherhood Hall in downtown Berkeley. This scenario surprises few in the know about

Italian American social clubs [3].

Only one Italian American business remains (a popular deli) in what used to be a thriving Italian business district. The Temescal’s Italian past is otherwise rather hidden: the backyard of many houses are full of fruit trees, and if you come across one of the rare California bungalows with a

basement you might be so lucky to find the remains of what was once a second kitchen [5]. Both sure signs of the Italian families who once lived there.

More recently the neighborhood has become the heart of Oakland’s East African population, with residents hailing mainly from Ethiopia and Eritrea. This has created another interesting Italian presence to the neighborhood, albeit one infused with Italy’s colonial past.

But let’s get back to Brooklyn, or more to the point, New Jersey, being that my trip to Brooklyn was sandwiched between visits to Long Island and New Jersey. Which brings me to Soprano Country—Bloomfield, Clifton, and North Caldwell. I saw it all. But what really stuck with me is how ubiquitous Italian American life is in the area (not just New Jersey or Long Island, mind you; I took a jaunt down Brooklyn’s Court Street and Avenue U, too, and saw plenty of pasticcerie and salumerie, not to mention other subtle, or not so subtle, signs of Italian American existence).

What struck me is the way a small town, like, say, Nutley, New Jersey, seems to have become (or always was?) a kind of Little Italy all its own. That when Italian Americans did their part in the great white flight to the suburbs in the decades following the Second World War, those in the New York area appeared to have taken a good part of the commerce and culture of their urban neighborhoods with them. (I realize I’m making some broad generalizations here.)

This phenomenon did not happen in California, even though the state had a number of Italian American urban neighborhoods that disappeared or drastically changed when Italian Americans moved out of the cities. Why does Italian American identity remain intact more recognizably in Eastern suburbs?

However, there’s a more interesting possibility, one that requires much more careful study than is called for in a simple blog post: that is, the role of the (often-overlooked) second major wave of Italian immigration to the U.S. after the Second World War. Sure, California received its share of post-WW II immigrants (and they’re still coming today—Silicon Valley is full of Italians with H1-B visas), but not to the same degree as on the East Coast. Further—and yes, I’m being a little coy here—but I’ll take a wild guess that the influx of new immigrants in the post-war decades reinvigorated Italian American communities in greater New York in multiple ways: from customs around food, to the use of Italian and dialects, to all sorts of vernacular displays of culture.

Let’s get specific, or maybe I’m just turning to the mundane. For example, I was surprised at how much Neapolitan I heard walking around Nutley and at the ways the local Nutley supermarket, a Shop-Rite, caters to an Italian American clientele.

The store finds it necessary to describe canned tomato products in so many different ways (I won’t even get into the fact that in California “gravy” is something one puts on turkey).

I couldn’t resist snapping these photos. I was shocked to see so much locally-made mozzarella as well as Italian pastries (who knows if they were any good, but items such as these in the Bay Area are only to be found in upscale grocers and specialty food stores).

Moments after I took these pictures I was stopped by a plainclothes guard wondering what I was up to. When I explained my interest and academic background, the sfogliatelle came out of the case for me.