9/11: Experiencing it First Hand to Believe?

It’s now almost become a rite to share what we all remember, we the inhabitants of the western part of the planet, where we were and what we were doing on September 11, 2001. As if it were necessary to take a turn as a protagonist in order to give proper significance to the event. The significance becomes even more important for us because it takes on a personal meaning. Personal more than global. After ten years since the collapse of the Twin Towers it is worthwhile to take a look inside and reflect on the impact that event had on our lives.

September 11 on television was something different from the other media event often mentioned in communications textbooks: the live broadcast of “intelligent” bombing in Iraq. I was in Naples then; I saw them on a screen during a peace demonstration. They made an impression, yes, but they also seemed so far away, almost staged: there were missiles but not people who were hit. Then there was the war and “luckily” I lived in a country at peace.

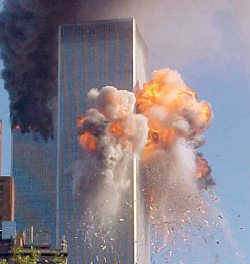

With the attack on the Twin Towers, the West saw a live broadcast of something different: human beings affected in their everyday lives, in a city at peace; bodies that leapt into the void to escape the flames.

September 11 is associated with many words: terrorism, war, death, fear. I particularly agree with two that have changed basic perceptions in the Western world: insecurity and personalization.

Insecurity. It started at that time and has only increased since then, now overflowing. From insecurity due to fears of more terrorist attacks to the economy.

Personalization. After the September 11, death is seen and experienced; it is made up of people, shattered into stories. It has its own epic series, live on TV. We saw “real people” falling from the towers. They were recognized; they were followed one by one in the images their friends and relatives saw broadcasted in every corner of the city.

We immediately began to breathe a personal fear in our suspicious glances at people on the street, in the subway, in schools, in airports. Red, orange, yellow alerts and then the spread of terror between Europe and the United States.

And we all started to wonder about the red thread that binds the safety of our daily lives with the decisions of the powerful people in this world—and their enemies.

I am an almost-witness, a person who narrowly missed the physical attack on September 11. Five minutes later and I would have found myself there at that moment, under those towers. And the story with a capital S would not have missed me, but touched me. Captured me, so to speak.

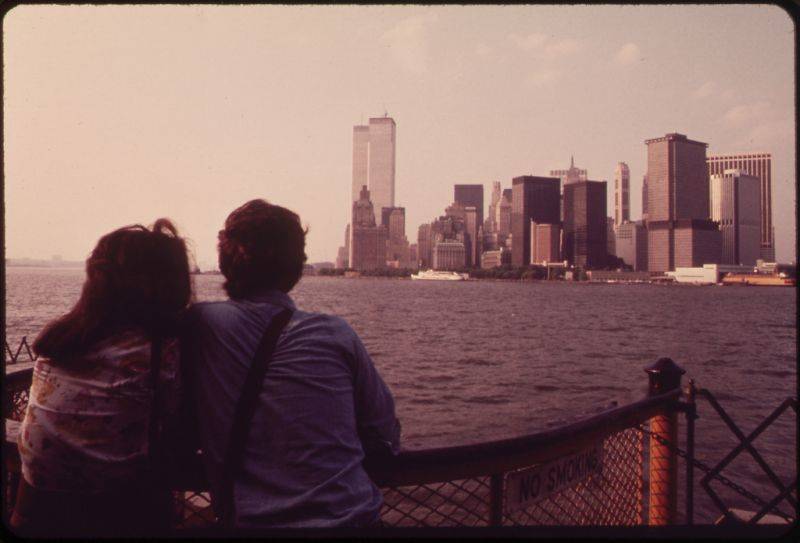

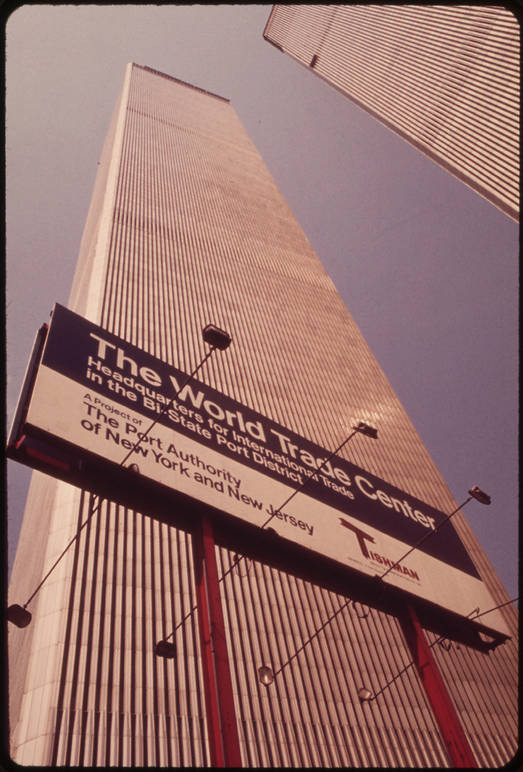

I lived in front of the WTC and I was in the middle of the Twin Towers boarding the Path, the train that took me to the opposite bank of the Hudson River in New Jersey to work. It was a habit marked by a ritual that I repeated every day. The over-crowded stairs and corridors led me to the train. I was walking against the tide, obviously because most people were going in the opposite direction, from New Jersey to New York, during the usual morning commute.

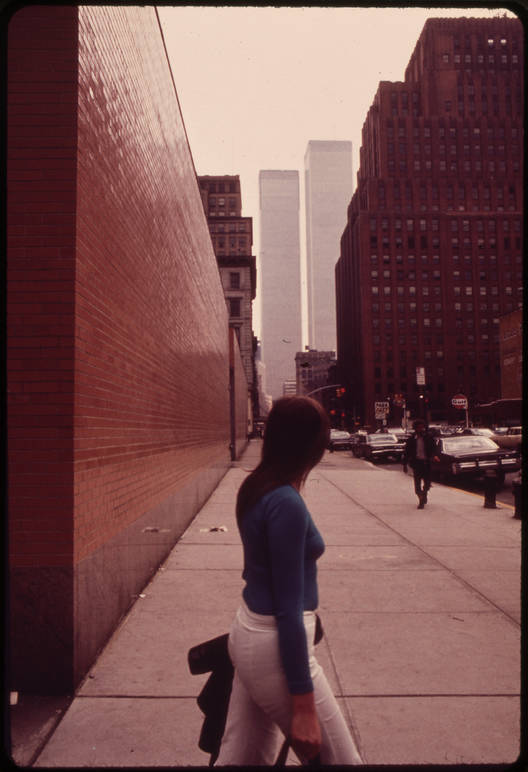

A stream of people kept coming at me—men, women mostly in business suits and sneakers, children, young people of every race, ethnicity, religion. All in a hurry, but with eyes filled with life, by the light of a city that knows how to give so much to those who ask.

Slowly I learned how to navigate the countercurrent: I brushed passed them gently. In the spaces I went through there were several kiosks managed for the most party by people from Asia. In particular I remember a florist. I always thought that I would buy one of her beautiful bouquets on my way back, but I never did. And of course I didn’t on September 11.

With hot coffee in hand, purchased from an Indian vendor, I was in a hurry and left all of this behind; even Borders, then my favorite bookstore where I often spent long hours over the weekend.

I would wake up every morning to the routine of meeting of faces, features, shapes unknown but familiar, repeated day after day. I sometimes even recognized the clothing these strangers wore, the details in their accessories.

I took the escalators down to take that train, an umbilical cord between the two shores of the Hudson. The bell rang, the doors were closing, and I left.

From 9/11 at the WTC I remember the sun coming through, a spring day in September. Then, as always, there was the descent into the unnatural darkness of the Path train which runs through the underwater tunnel and re-emerges in New Jersey.

My mind is still struck by the faces of those people, many of Hispanic ethnicity. Their eyes were often closed, their heads bobbing and sometimes falling onto their neighbors’ shoulders only to wake up in a flurry of a thousand apologies.

That day I was just in time to overcome the darkness. The light dazzled me again and I got off the train in Newark to enter a skyscraper and go up to the 26th floor. There. High up. With my eyes, together with other people, stunned, I saw what was happening live at the Twin Towers. The radio confirmed it. The United States was under attack.

From that moment my memories, I confess, piled up in confusion. I was in the throes of some form of intoxication from reality, worse than the worst nightmare and gripped by fear and terror for those who I had left near the towers.

Everything was fine in terms of my own family, fortunately, but not for so many others who I knew and many more who I did not know. And ten years is still not enough time to process it.

Stranded in New Jersey for 24 hours, I finally returned to Manhattan, but not home, which was inaccessible for nearly a month. Even after I returned, for many months afterwards my entire building was engulfed by the smell of death and disinfectant.

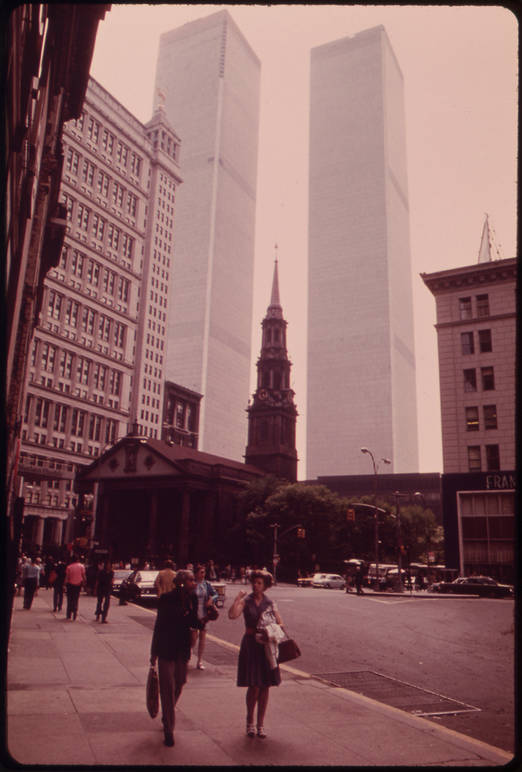

And death was not only the death of others. It was the death of my neighborhood. It was the death of everyone near and far. It was a feeling that perhaps my grandmother had described to me when I was a child and she spoke of the bombings during the Second World War.

In Manhattan the photos of the missing, posters designed by families and friends, told the private lives of those people. Their stories and everyone’s stories. A newspaper took its cruel revenge. Shameless in its spectacle. This was a real reality show, not the kind created at a conference room table that we would see a few years later. The message was clear: death penetrates every corner of the world. We are not in a video game!

Everyone’s concern and involvement filled the heart of New York. In those days the city’s profound suffering sent a message of insecurity to the world, forever changing the feel of our collective history. It put an end to the easy optimism which many experienced after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

There was talk of the end of the United States’ inviolability, but in hindsight, after ten years of so much uncertainty, we can see something more: a sort of worldwide awakening. Affected families, friends of the victims, but also an attack on the whole of humanity in its absurd presumption of certainty.

New York in those days knew how to make people talk, how to bring people together, even if fear still reigned. This happened partly because New Yorkers were embraced by the Western world; they had become people with hearts and they looked into each other’s eyes. New Yorkers were not characters in a popular television series broadcast around the world. Remember Sex and the City? The New York that belonged to Carrie and her friends had traveled around the world. That was the image many had of Manhattan at that time.

After 10 years since that tragic day, after trying to consider everything that has happened since with a bit of detachment, from wars to social, economic, financial, and political upheaval, many continue to question the actual impact of the collapse of those towers.

There are many hypotheses.

I want to come back to what it meant to realize that we are people and not just spectators. September 11 was perhaps the first time when one particular event, which for many took place far away, has been incised into the personal lives of so many different Western countries at the same time. It has intimately marked our consciousness.

“Do you remember where you were on September 11?” I believe that in this case this question is so much more than a cliché. It’s true: people always ask, “Do you remember where you were when John F. Kennedy was shot?” But the assassination of an American president remained altogether distant even if it changed the course of history, not only American history but world history. And it perpetuated JFK’s myth from a distance.

September 11, instead, in some way belongs to everyone. We have lived it, personalized it. It is nevertheless true that we must identify and empathize with suffering in order to understand it. If not, we will continue to unleash, indifferently, even more famine and war on the world which continues to get smaller.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.