Living by Addition

The event at the Italian Cultural Institute in Manhattan was billed as An Evening with "Italian" Writers. The quotation marks around "Italian" were suggestive – what is an "Italian writer"? – but also appropriate given the evening's two featured authors, whose mixed identities render them "italiano ma non italianissimo" (Italian, but not very Italian), as one of them remarked.

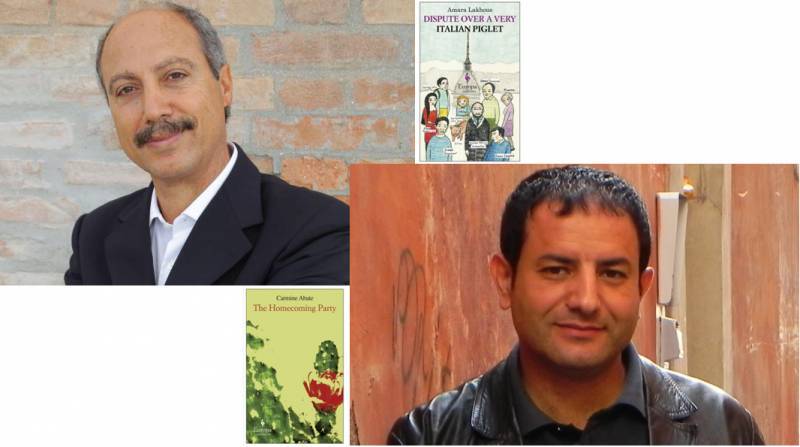

The Institute hosted a panel on April 7 with Amara Lakhous, an Algerian who has become abest-selling author in Italy, and Carmine Abate, born in Calabria to an Arbëresh-speaking family. Both writers experienced immigration (Abate moved to Germany when he was a young man), both are members of ethnic and linguistic minorities, and both regard their diverse backgrounds as assets. At the Institute, they spoke about the complexities of language, ethnicity, and national identity, and how they address these themes in their work.

Of the two, Amara Lakhous is better known to Anglophone readers; three of the novels he has published in Italy are available in English translations. Abate, a novelist, poet, and short story writer, is highly regarded in Italy and Europe, but only two of his many works have been translated into English. During the panel discussion, Abate spoke in Italian with a translator by his side; Lakhous spoke in English, which he has only recently learned. Michael Reynolds, who edited the English translations of both authors' books for the independent publisher Europa Editions, marveled that "only six months ago we wouldn't have been able to have this conversation" with Lakhous in English.

Lakhous was born in Algeria in 1970 to a Berber-speaking family; he learned Arabic at school. (His mother, he remarked, still does not speak Algeria's main language.) He worked as a journalist for Algerian radio but fled to Italy in 1995 after Islamic extremists threatened his life.

He brought with him a manuscript he had written in Arabic; it was later published in Italian under the title, Le cimici e il pirata (The Bedbugs and the Pirate). His second novel published in Italy, Scontro di civiltà per un ascensore a Piazza Vittorio (Clash of Civilizations over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio), was a 2008 bestseller and won the prestigious Flaiano Prize. The novel, inspired by his experiences in Rome's multiethnic Piazza Vittorio neighborhood, where he lived for six years, uses a murder mystery to examine how people from many different backgrounds coexist, in a multicultural environment.

Lakhous remarked that the novel's success made him so well known in Rome that when he applied for Italian citizenship, the bureaucrat handling his application quoted his novel's title to him.

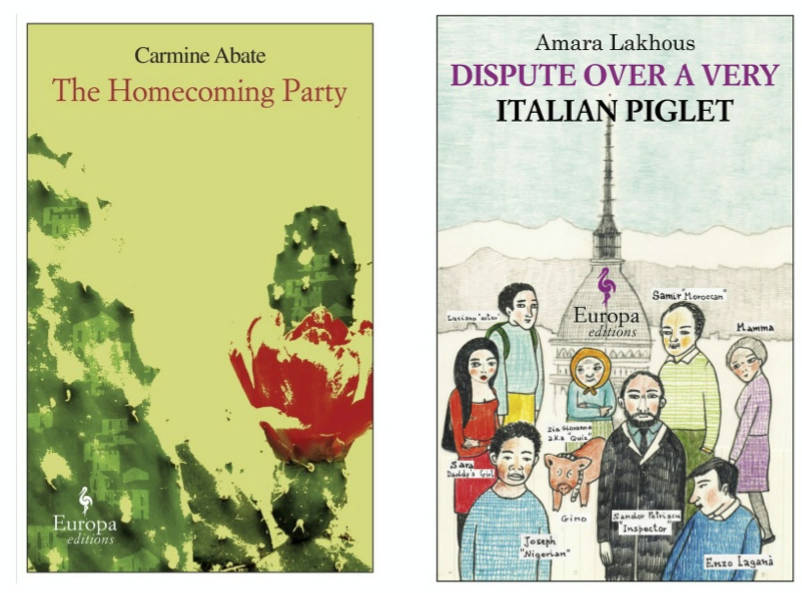

Since then, Lakhous has published two more novels, both available in English translations from Europa Editions: Divorce Islamic Style (2012) and Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet (2014). He somehow managed to find the time to earn a degree in cultural anthropology from Rome's La Sapienza University; his dissertation focused on Muslim immigrants in Italy. Before coming to Italy, Lakhous earned a degree in philosophy from an Algiers university. He remarked that his training in both disciplines, and in journalism, had served him well as a fiction writer.

Carmine Abate was born in 1954 in Carfizzi, an Arbëreshë village in Calabria. At home, he spoke Arbëresh, a variant of Albanian. (The Arbëreshë descend from Albanian Christians who fled to southern Italy in the late fifteenth century to escape Ottoman invaders.) Abate remarked that the Arbëreshë established 100 towns in Italy, in every southern region except Sardinia. Of these, fifty remain.

He said that he learned Italian as a schoolboy, an experience he called "traumatic" because teachers would beat students' hands with a stick if they spoke Arbëresh. After graduating from the University of Bari, Abate moved to Hamburg, where his father had earlier emigrated. While teaching at a school for immigrants, he published his first short stories. After more than a decade in Germany, he returned to Italy, settling in Trentino, where he continues to live and work.

Abate has published several acclaimed novels and short story collections. Europa Editions has published his novels Tra due mari (Between Two Seas) and La festa del ritorno (The Homecoming Party) in English translations by Antony Shugaar. Both are set in Calabria, the second in an Arbëreshë town very much like Abate's Carfizzi. His more recent works, in Italian, include Terre di andata: Poesie e proesie (2011) and La collina del vento (2012); the latter won the Campiello Prize for literature.

Speaking about growing up in Carfizzi, he remarked, "I don't see myself as different from other Calabrese except for language." His upbringing was unique, though, in that three languages were spoken in his home: Arbëresh, English (his grandfather had spent some time in the U.S.) and German, or rather, what he called "germanese," the immigrant dialect his father spoke when he lived in Germany. Arbëresh, however, was "the language of the heart," which he distinguished from Italian, "the language of bread," that is, the dominant language one must speak to assimilate and earn a living.

A "Mosaic" of Identity

Amara Lakhous and Carmine Abate met for the first time in 2006, and they felt an immediate kinship, as Mediterranean writers who believe that being members of ethnic/linguistic minorities has proved advantageous to their literary careers. "When you are part of the majority, you are very protected. You have all the answers, the language, the religion. When you are part of a minority it's more complicated, more challenging, because you have to find new solutions," Lakhous observed.

Abate said he preferred to speak of plural identities, using the metaphor of a mosaic to describe one person who carries many cultures and who chooses "the best" from each. "Living by addition," he called this polyvalent condition, alluding to the title of his 2010 short story collection, Vivere per addizione e altri viaggi.

Lakhous said that when he met Abate, he already had read the Calabrian's books. In one of them, he recognized his own father and family. He called Abate "one of the most original Italian writers" and a "master of narrative."

He noted, however, that there were differences between them. He called himself a "bilingual writer" who writes in Italian and in Arabic. Abate writes only in Italian – for him, Arbëresh is a spoken language – but he "thinks" his work in his native tongue and then "turns it into Italian."

Lakhous mentioned that he is writing a new novel in Arabic; Abate said he is studying English while working on a novel set in the United States. He added that he hopes to become sufficiently fluent to speak in inglese the next time he appears at the Italian Cultural Institute.

Speaking of national identity and citizenship, Lakhous said that he has "constructed an Italian identity" that he called "italiano, ma non italianissimo." He remarked that the Italian he uses in his books is a language "I learned in the streets, talking to people." He added that he found in the Italian language "a new homeland, a new mother." But the Italian of his books often is a hybrid tongue that incorporates Arabic words. As he once remarked, his aim as a writer is to "Arabize the Italian and Italianize the Arab."

Lakhous, an Italian citizen since 2008, cited the ongoing controversy in Italy over the status of Italian-born children of immigrants. Like in other European countries, Italian citizenship is based mainly on jus sanguinis – literally, right of blood – meaning that it is determined not by place of birth but by having one or both parents who are citizens. A child born to immigrant parents doesn’t automatically acquire Italian citizenship; it must be requested, and before the child is eighteen years old. The application and review processes can drag on for years before citizenship finally is granted.

Italian law, however, makes it easier for people from the Italian diaspora to become citizens, which rankles Lakhous. Like other critics, he finds it unjust and discriminatory that descendants of Italian immigrants in the U.S., Latin America, Australia, and elsewhere – many of whom do not speak Italian and have no organic connection to Italy – can obtain citizenship more easily than do children of immigrants who were born in Italy, speak the language, and know no other homeland.

Lakhous said he was pessimistic about the situation changing. Right-wing parties, and especially the Northern League, feed and exploit anti-immigrant attitudes. The League's leader, Matteo Salvini, has been trying to win support for his party's xenophobic program even among southern Italians, whom the League traditionally has disparaged almost as much as immigrants.

"We [reform advocates] are losing in Italy today," Lakhous sadly concluded.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.